This is a round-up of various types of online information ranging from blogposts to newspaper articles to announcements of books and e-books.

I’ll begin with books that have recently appeared. These relate to Senchus topics and have been written by people who have commented on past blogposts here. In no particular order….

Hot off the press is The Chronicles of Iona: Exile by medievalist and blogger Paula de Fougerolles. Launched last month at The Haven (‘Boston’s first and only Scottish pub’) it tells through the medium of historical fiction the story of St Columba’s dealings with the early Scottish king Áedán mac Gabráin. Back in March in a roundup from the blogosphere I gave advance notice of this book, which is now available in print and electronic formats. The second volume in the Chronicles of Iona series is already in the pipeline. Check out Paula’s blog to keep up to date with her writing, or follow her on Twitter at @PaulaDeFoug

‘Seventh century Britain is in transition. Small kingdoms are dissolving and merging…..’ This is the volatile world in which a young Anglo-Saxon woman, the future St Hild of Whitby, is set to play an important part. Hild is the subject of Nicola Griffith’s eponymous novel which is due to be published in New York in the autumn of 2013. Nicola has an impressive track record as a prize-winning author so we know the narrative is in safe hands. In addition, I can vouch for her depiction of seventh-century North Britain as meticulously researched and as historically accurate as it’s possible to get. Those of you who use Twitter will find Nicola at @nicolaz or you can follow the progress of Hild via the Gemaecca blog.

Also newly published is The Last of the Druids: the Mystery of the Pictish Symbol Stones by Iain Forbes. This is another book I mentioned as forthcoming back in March, when I posted a link to the striking cover which shows the Hilton of Cadboll cross-slab. Out in the Twittersphere, where Iain is @IainForbesPict, he and I frequently provide our respective followers with links to pictures of Pictish stones and bounce each other’s tweets to and fro. Iain’s blog is also worth a look if you’re interested in the Picts. It currently has a nice post about the stone from Shandwick in Easter Ross.

[This paragraph was updated in January 2015] Mak Wilson is working on an e-book about the historical figure behind the legends of King Arthur. The book asks the fundamental question at the heart of the debate: Fact? Fiction? or Confusion? Mak has posted extracts at his new blog (his old Badonicus site no longer exists). If you’re a frequent visitor to Senchus you’ve probably seen Mak’s comments in various threads here. Mak’s on Twitter too, as @MakWrite.

Richard Denning will be a name familiar to those of you who follow the comment threads on my blogposts dealing with the Battle of Degsastan. At Richard’s website you’ll see information on his historical novel The Amber Treasure which is set in the era of the battle. Here’s a synopsis of the story… 6th Century Northumbria: Cerdic, the nephew of the great warrior Cynric, grows up dreaming of glory in battle and writing his name in the sagas. When war comes for real though, his sister is kidnapped, his family betrayed and his uncle’s legendary sword stolen. It falls to Cerdic to avenge his family’s loss, rescue his sister and return home with the sword.

Child of Loki, Richard’s second novel about sixth-century North Britain, is also available. In addition, Richard gives his views on Degsastan on the website English Historical Fiction Authors. You can follow him on Twitter where he’s easily recognisable as @RichardDenning

The Viking Highlands – The Norse Age in the Highlands by Dave Kelday is an e-book which looks at one of the most turbulent periods in Scottish history. The description at Amazon says that the author “aims to present a coherent, historical, sometimes speculative, narrative of that long era in Highland history when the people, politics and culture of the Norse played such a vital and significant role in the life and development of the nation.” I’m no stranger to weaving a historical narrative from scattered fragments of data, having used the same technique in my own books. In an email conversation Dave told me he used controversial texts such as the Norse sagas and the Manx Chronicle in this way while keeping in mind their limitations as historical sources.

Moving seamlessly from books and e-books to blogposts, online essays and news items…….

Most of you will know by now that Scotland has been given the Disney/Pixar treatment in a new animated feature called Brave. It looks good and is already out in the US. Michelle Ziegler went to see it and has put up a useful review at her Heavenfield blog. I hope to see Brave in the not-too-distant future and will probably review it here.

Do you remember my series of posts on the origins of Clan Galbraith? One contributor to the comment threads was Peter Kincaid who runs the website kyncades.org which explores the history of his surname. Peter has written an interesting paper on King Coroticus, the slave-raiding warlord castigated by St Patrick for capturing young Irish Christians and selling them to the Picts. One Irish tradition associated Coroticus with Aloo, usually interpreted as a garbled Gaelic form of Alt Clut, the Rock of Clyde at Dumbarton. Peter questions this identification and offers an alternative theory which suggests that Aloo might refer not to a place but to a military unit.

What nationality was St Cuthbert? Being interested in matters of ethnicity and identity in early medieval times it’s the kind of question I like to explore. I’m grateful to Liz Roberts for pointing me to a letter on the Telegraph website suggesting that the answer to this question should not necessarily be ‘English’. It is possible that Cuthbert was as much a Scottish saint as an English one, or maybe we should simply call him ‘Northumbrian’. I know from speaking to Liz that she has her own views on the use of ethnic terminology relating to this period. She’s right to be concerned about it. Terms such as ‘Scottish’ and ‘British’ are sometimes bandied about quite casually in reference to the early medieval period, without much thought being given to what they really meant a thousand years ago.

Here’s another question: where did the Picts defeat the Northumbrians on 20 May 685? The vicinity of Dunnichen Hill in Angus is seen by many as the likeliest location, but Dunachton in Badenoch is another candidate. Either or neither of these places could be the hill (or hillfort) called Dun Nechtáin in the Irish annals. The uncertainty means that the best-known event in Pictish history cannot be listed in an official inventory of battlefields. Historic Scotland’s decision to exclude Dunnichen from the list has not gone down too well in Angus, as this news item from The Courier makes clear.

Further west, in the Hebridean seaways, an archaeological excavation has recently commenced on the island of Eigg, its aim being to discover the origins of the ecclesiastical site at Kildonan. This is supposedly where St Donnan established a monastery in the late sixth century. He and his monks suffered martyrdom in 617 when the island was attacked by pirates. Because of the importance of the site I’ll be following the progress of this excavation closely. At some point I hope to run a blogpost about it.

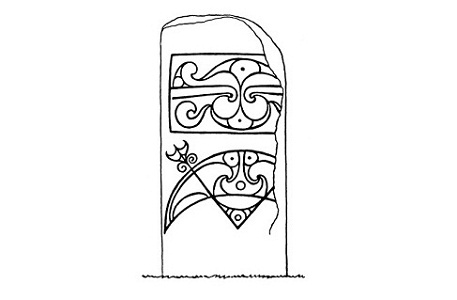

Another excavation is hoping to unravel the mystery of Trusty’s Hill, a site overlooking the Solway Firth, where Pictish symbols are carved on a rock at the summit. Why are these carvings found here, so far away from the Pictish heartlands? Who occupied the fort on top of the hill? This was territory ruled by Britons, not Picts – or so conventional wisdom tells us. Yet the name Trusty seems to relate in some way to Tristan, and both may derive from the Pictish name Drostan, so are we looking at a genuine connection with the Picts?

Finally, but not for the last time, I recommend a visit to Heavenfield where Michelle has recently posted her latest round-up from the medieval blogs as well as the above-mentioned review of Brave. If you’re a ‘tweep’ you can follow Michelle on Twitter where she’s @MZiegler3. I’m a twitterer as well, in two guises: @EarlyScotland and @GovanStones. Speaking of Govan, I’ll be giving an update on what’s been happening there in my next blogpost, which will be published here at Senchus rather than at Heart of the Kingdom.

* * * * * * *