‘Ruled from Govan, the ancient kingdom of Strathclyde stretched from Clydesdale to the Solway Firth. This book is the first to shed light on it and its ruling dynasties. A must for all interested in medieval history.’

(Scots Magazine, April 2015)

* * * * * * *

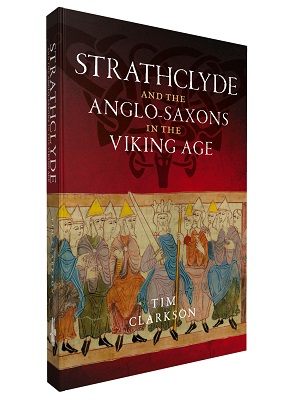

My fifth book on early medieval Scotland was published this week.

Strathclyde and the Anglo-Saxons in the Viking Age traces the history of relations between the Cumbri or North Britons and their English neighbours through the eighth to eleventh centuries AD. It looks at the wars, treaties and other high-level dealings that characterised this volatile relationship. Woven into the story are the policies and ambitions of other powers, most notably the Scots and Vikings, with whom both the North Britons and Anglo-Saxons were variously in alliance or at war.

As well as presenting a narrative history of the kingdom of Strathclyde, this book also discusses the names ‘Cumbria’ and ‘Cumberland’, both of which now refer to parts of north-west England. The origins of these names, and their meanings to people who lived in Viking-Age Britain, are examined and explained.

The book’s main contents are as follows:

Chapter 1 – Cumbrians and Anglo-Saxons

A discussion of terminology and sources.

Chapter 2 – Early Contacts

Relations between the Clyde Britons and the English in pre-Viking times (sixth to eighth centuries AD).

Chapter 3 – Raiders and Settlers

The arrival of the Vikings in northern Britain, the destruction of Alt Clut and the beginning of the kingdom of Strathclyde or Cumbria.

Chapter 4 – Strathclyde and Wessex

Contacts between the ‘kings of the Cumbrians’ and the family of Alfred the Great.

Chapter 5 – Athelstan

The period 924 to 939 in which the ambitions of a powerful English king clashed with those of his Celtic and Scandinavian neighbours. Includes a discussion of the Battle of Brunanburh.

Chapter 6 – King Dunmail

The reign of Dyfnwal, king of Strathclyde (c.940-970) and the English invasion of ‘Cumberland’ in 945.

Chapter 7 – The Late Tenth Century

Strathclyde’s relations with the kings of England in the last decades of the first millennium.

Chapter 8 – Borderlands

The earls of Bamburgh and their dealings with the kings of Alba and Strathclyde. Includes a discussion of the Battle of Carham (1018).

Chapter 9 – The Fall of Strathclyde

The shadowy period around the mid-eleventh century when the last kingdom of the North Britons was finally conquered.

Chapter 10 – The Anglo-Norman Period

Anglo-Scottish relations in the early twelfth century and the origin of the English county of Cumberland.

Chapter 11 – Conclusions

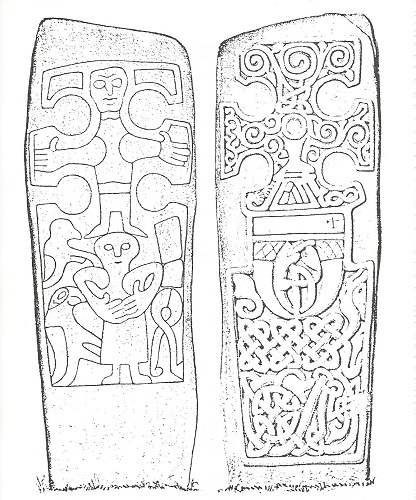

Notes for each chapter direct the reader to a bibliography of primary and secondary sources. Illustrations include maps, photographs and genealogical tables.

Published by Birlinn of Edinburgh, under the John Donald imprint, and available from Amazon UK and Amazon USA.

* * * * * * *