Ten years have passed since the publication of my book The Men Of The North: The Britons Of Southern Scotland. It has since been reprinted a number of times, becoming unavailable for only brief intervals between reprints. For an author, this is an encouraging situation to be in, and I am grateful to my publishers (Birlinn of Edinburgh) for keeping the book ticking over throughout the decade. I am also grateful for the many positive comments from readers and reviewers, all of which have encouraged me to believe that the effort of researching and writing this book has not been in vain. Of course, no book is going to please everyone, and The Men Of The North is no exception. On the whole, though, it seems to have been generally well-received.

“Until the publication of The Men of the North there had never been a textbook for the North British kingdoms — its appearance should be welcomed by undergraduates, teachers, and the general public alike.” Dr Philip Dunshea (International Review of Scottish Studies, 2012)

The above quote, from a Scottish historian whose opinions I value highly, captures in a nutshell my main reason for writing The Men Of The North: I saw a gap on my bookshelf and decided to have a go at filling it myself. Ever since my first forays into early medieval history in the 1980s, I had become increasingly aware that the Northern Britons are Scotland’s forgotten people. They are far more obscure and mysterious than any of their neighbours (including the supposedly enigmatic Picts) and their significant role in Scottish history has frequently been overlooked. References to them in medieval chronicles are thin on the ground, leaving huge gaps in their story and forcing modern historians to scrabble around for snippets of information in less reliable sources (such as poems and legends). Nevertheless, I had often wondered if the various fragments could be assembled into a more-or-less coherent narrative, a stable framework around which a chronological history might take shape. It was 2009 before I took the plunge by putting pen to paper and fingertip to keyboard. The task was as challenging as I had expected it to be, but the result was a book that I felt passed the test.

The Men Of The North includes my own interpretations of certain parts of the textual evidence. This is especially true in the first half of the book, which draws data from medieval Welsh poems in which the deeds of various sixth-century North British kings and warriors are praised. Ten years later, and I can report that these interpretations remain largely unchanged. I still firmly believe that the locations of Rheged (a kingdom, or part of one) and Catraeth (apparently the site of a battle) remain unknown. I still reject the conventional notion that four North British kings joined together in a military coalition to launch a combined assault on an English royal dynasty whom they besieged or blockaded on the island of Lindisfarne. In this particular instance, I see each British king waging his own campaign independently of his alleged allies. If my views on these topics have changed at all in the past ten years, they have probably hardened rather than softened.

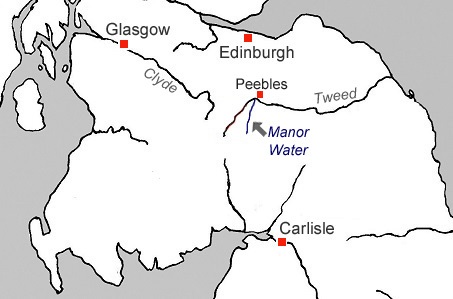

Some of my views have, however, shifted somewhat. On page 178 of The Men Of The North, while discussing the question of where the great battle of Brunanburh (AD 937) was fought, I mentioned three places as popular candidates for the battlefield. These were Bromborough in Wirral (Cheshire), Burnswark in Dumfriesshire and Brinsworth in South Yorkshire. I now favour a location in Lancashire, either near the estuary of the River Ribble or further east around Burnley. This revision of my thinking is presented in detail in my second book on the Northern Britons, published in 2014 under the title Strathclyde and the Anglo-Saxons in the Viking Age.

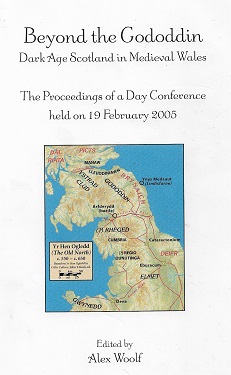

Several people have asked if a new edition of The Men Of The North is in the pipeline. My response is that there are, as yet, no definite plans. If a second edition does appear at some point in the future, it will undoubtedly make much use of another book, an edited volume called Beyond The Gododdin, published in 2013 by the Committee for Dark Age Studies at the University of St Andrews. Indeed, I would go as far as to say that no new research on the North British kingdoms of the sixth century should be regarded as complete unless the papers in Beyond The Gododdin have been consulted and cited.

Any new edition of The Men Of The North will also cite the publications of Dr Fiona Edmonds, author of several ground-breaking papers on the Viking-Age kingdom of Strathclyde/Cumbria, last of the North British realms. As with the contents of Beyond the Gododdin, I regard the work of Dr Edmonds as essential reading. I recommend, in particular, two journal articles and one book chapter. Bibliographic details for these three are given in the list of references at the end of this blogpost.

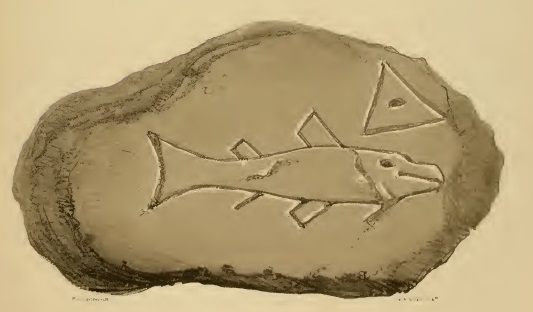

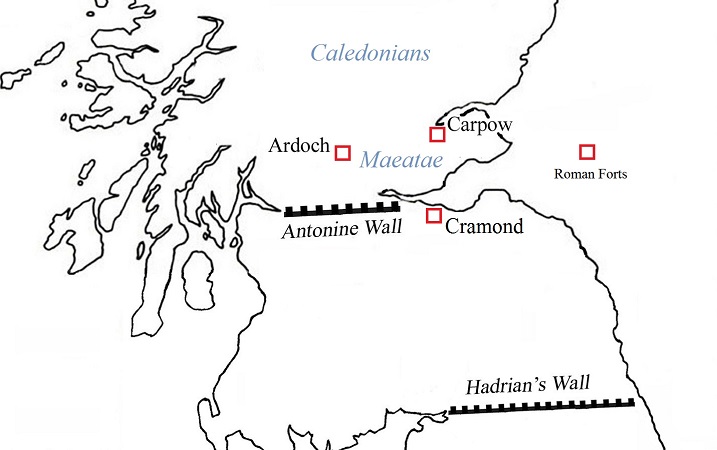

The past decade has seen other new publications relating to the Northern Britons, too many to list here. I must, however, mention a major archaeological report produced as part of the Galloway Picts Project. Published in 2017, this substantial monograph gives the results of a programme of excavation at Trusty’s Hill, site of a hilltop fortress famous for mysterious carvings that look like Pictish symbols. Interestingly, the report’s main title is The Lost Dark Age Kingdom Of Rheged, reflecting the authors’ belief that Trusty’s Hill is a good candidate for Rheged’s main centre of royal power. Although I remain open-minded on this claim of a Rheged connection, there can be no doubt that the report represents a big contribution to our archaeological understanding of the Northern Britons, giving us an insight into what must have been one of their principal high-status settlements.

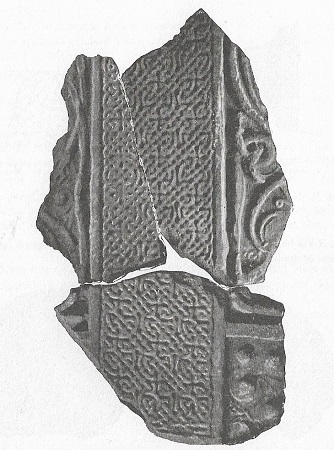

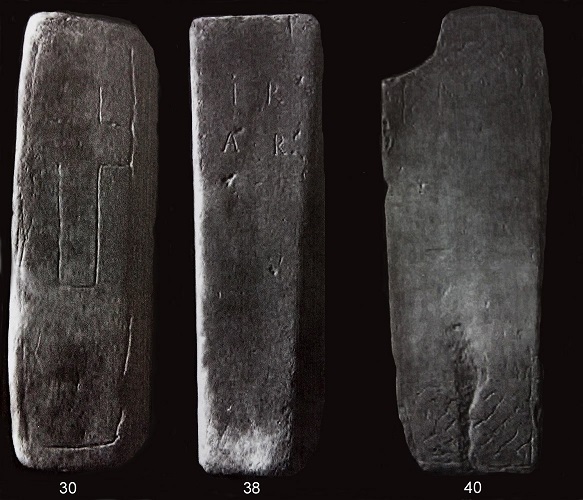

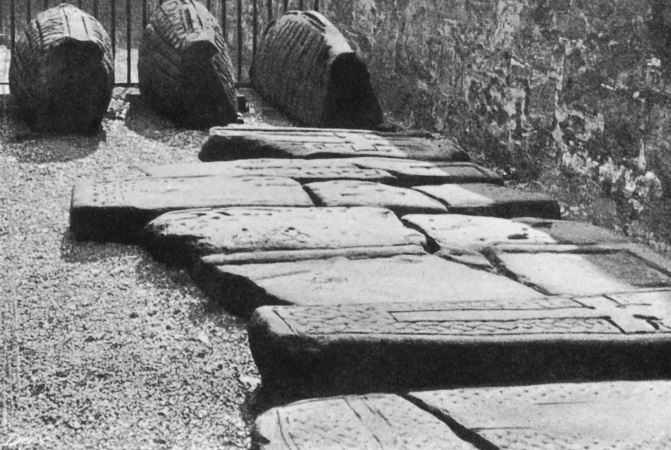

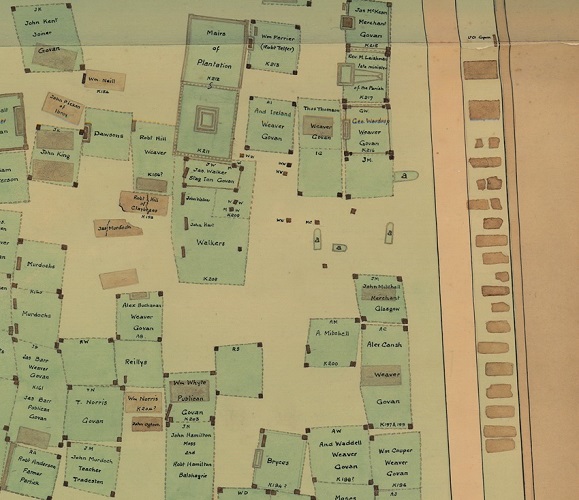

On a personal level, the biggest change in my involvement with the Northern Britons since 2010 has been my participation in a number of local heritage projects at Govan on the south side of Glasgow. Most of these projects had a connection with the Govan Stones, a collection of sculptured monuments displayed in the old parish church. The stones were carved in the ninth to eleventh centuries when Govan was a centre of ritual and authority in the kingdom of Strathclyde. The heritage projects helped to raise awareness of the stones not only among the local community but more widely across Scotland as well as internationally. When I first came aboard in 2012, there were some thirty monuments to be seen. Three others, thought to have been lost, were unearthed last year (as I reported at this blog — see link below). Like the archaeological data from Trusty’s Hill, the rediscovered stones at Govan will be studied and analysed, and the information will increase our knowledge of early medieval Scotland.

The Govan Sarcophagus

Banner outside Govan Old Parish Church where the stones are displayed

I expect the next ten years will yield further new information on the Northern Britons, whether in the form of archaeological discoveries or re-interpretations of historical texts. It will be interesting to see if The Men Of The North gets left behind, like something outdated and obsolete, and whether a revision or update then becomes desirable for author and reader alike. If this is what happens, and if I haven’t made a start on a second edition by September 2030 (the book’s twentieth anniversary), I may need someone to give me a not-too-gentle nudge.

* * * * *

Links :

My blogpost from September 2010, announcing the publication of The Men Of The North.

The first review of The Men Of The North, at Michelle Ziegler’s Heavenfield blog.

My blogpost from 2019 on the carved stones rediscovered at Govan.

My sceptical views on a supposed ‘coalition’ of sixth-century North British kings at Lindisfarne.

My book review of Beyond The Gododdin for the journal Northern History, available online at my Academia page.

* * *

References :

Tim Clarkson, The Men Of The North: the Britons of Southern Scotland (Edinburgh, 2010)

Tim Clarkson, Strathclyde and the Anglo-Saxons in the Viking Age (Edinburgh, 2014)

Fiona Edmonds, ‘The Emergence and Transformation of Medieval Cumbria’ Scottish Historical Review vol.93 (2014), 195-216.

Fiona Edmonds, ‘The Expansion of the Kingdom of Strathclyde’ Early Medieval Europe vol.23 (2015), 43-66.

Fiona Edmonds, ‘Carham: the Western Perspective’, pp.79-94 in Neil McGuigan and Alex Woolf (eds) The Battle of Carham: a Thousand Years On (Edinburgh, 2018).

Alex Woolf (ed.) Beyond the Gododdin: Dark Age Scotland in Medieval Wales (St Andrews, 2013).

Ronan Toolis and Christopher Bowles, The Lost Dark Age Kingdom of Rheged: the Discovery of a Royal Stronghold at Trusty’s Hill, Galloway (Oxford, 2017).

* * * * * * *