Sculptured portrait of a Roman lady, believed to be Julia Domna.

Anyone who seeks to discover Scotland’s early history through textual sources written more than a thousand years ago soon realises that ‘fake news’ isn’t a modern phenomenon. It has always served a useful purpose for its creators, as much in the first millennium AD as in our own era of digital communication and social media. Recognising false information for what it is, rather than taking it at face value, is likewise as much of a challenge when we’re reading an ancient chronicle as when we encounter an attention-grabbing headline on the internet. In some instances, even after having dismissed something written in the remote past as fake information – such as a legend masquerading as real history – we find it so fascinating that we want it to be true. This is what happened to me many years ago when I came across what seemed, at first glance, to be a curious fact – namely that the oldest known words attributed to a woman from Scotland were spoken to a woman from Syria.

The conversation in question supposedly took place sometime in the early third century AD, around the years 209/210. Our source is the Historia Romana (‘Roman History’), a multi-volume work penned by the contemporary historian Cassius Dio. At that time, the Roman emperor Septimius Severus was on active service in northern Britain, leading a military campaign beyond the Antonine Wall – the great turf barrier stretching between the firths of Forth and Clyde. His foes were unconquered native peoples in what are now Stirlingshire and Perthshire, specifically two large groupings or ‘tribal confederations’ – the Maeatae who lived adjacent to the Wall and the Caledonians to the north of them. These two had been causing a great deal of trouble, raiding southward into lands under Roman rule and returning home laden with loot. A recent wave of attacks had been serious enough to persuade the governor of Roman Britain to appeal directly to Septimius Severus for aid. The emperor had duly taken personal charge of a major effort to bring the marauders to heel. Arriving in Britain in 208, accompanied by his wife and their two adult sons, he led his huge army northward. His troops suffered considerable losses from guerilla warfare but eventually both the Caledonians and Maeatae negotiated peace treaties with him. Dio identifies one of the key figures on the Caledonian side as Argentocoxos, presumably a senior chieftain, whose Celtic name means something like ‘Silver Leg’. However, the ensuing truce turned out to be short-lived and a new round of hostilities soon began.

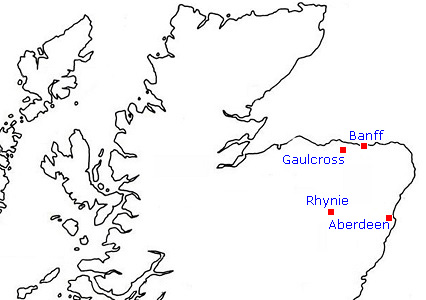

Severus in Scotland, AD 208 to 210, showing three of the many forts involved in his campaign.

According to Cassius Dio, it was during the brief period of peace that a conversation took place between the wives of Argentocoxos and Septimius Severus. The name of the Caledonian lady is unrecorded – perhaps Dio himself had no record of it. He certainly had no doubt about the identity of the other woman. She was Julia Domna, the Syrian wife of Severus and one of the most famous of all Roman empresses. Julia’s image was so well-known around the Mediterranean lands in her own lifetime that it can still be seen today on various coins, paintings and sculptures. Born c. 160 in the city of Emesa (now Homs) in Syria, she sprang from a high-status Arab family who seem to have had royal ancestry. Her father was a senior priest at Emesa’s Temple of the Sun, the main cult-centre of the Middle Eastern god Elagabalus. Charismatic and well-educated, Julia was a suitable bride for Severus when, as a childless widower in his early forties, he decided that he should be married again.

Septimius Severus, Roman emperor from AD 193 to 211.

Dio had a particular fascination with Julia and has left us a fair amount of information about her. As a career politician who served as senator and consul he was well-placed to obtain interesting snippets of information about members of the imperial family. He had rather less interest in barbarians like Argentocoxos, even when he could be bothered to name them. Like most Romans he no doubt regarded the inhabitants of ancient Scotland as a mob of wild, uncouth savages prowling beyond the Empire’s borders. As an author he nevertheless found them useful as caricatures of the stereotypical barbarian – simple, uncorrupted folk whose primitive ways of living could be amusingly contrasted with the immorality and hypocrisy of sophisticated Roman society. Drawing on such stereotypes, he informed his readers that the Caledonians and Maeatae ‘possess their women in common, and in common rear all the offspring’. It hardly needs saying that such a strange custom probably never existed among the contemporary inhabitants of Perthshire and Stirlingshire, nor are they likely to have viewed adultery and marital fidelity much differently from the citizens of Rome. The idea that they practised a kind of ‘free love’ may have originated as a joke or rumour among Roman soldiers stationed near the northern frontier – or perhaps Dio simply made it up. It appears in his narrative shortly before the meeting between Julia Domna and the wife of Argentocoxos and provides the essential moral backdrop to their conversation.

Dio tells us that the empress teased her companion by saying that Caledonian women indulge in a sexual free-for-all, sharing their beds with different men while making no attempt to conceal their adultery. To a respectable aristocratic lady like Julia, such brazen promiscuity would indeed have seemed worthy of comment. We then see the wife of Argentocoxos swiftly responding with what Dio calls ‘a witty remark’ of her own:

“We fulfil the demands of nature in a much better way than do you Roman women; for we consort openly with the best men, whereas you let yourselves be debauched in secret by the vilest.”

As with all ancient and medieval authors, we should be wary of taking Dio at face value. Although Julia Domna was very much a real person – and indeed one of his contemporaries – this did not deter him from portraying her in a way that suited his literary purposes. Modern scholars who analyse his writings believe that the Julia he presented to his readers was, to some extent, moulded to fit his narrative. There is no doubt that she plays a special role in the Historia Romana, particularly in those sections where Dio seeks to pass judgement on the moral and political issues of his time. In this instance, his target was not the allegedly shameless promiscuity of Caledonian women but the clandestine adultery of fine Roman ladies. The consensus view among present-day historians is that he simply invented the speech quoted above. Like a modern peddler of fake news, he took a piece of made-up information about a group of foreigners and ‘spun’ it to make a specific point. His readers – the wealthy, educated elite of the Roman world – would have got the message very clearly. Some of them probably raised a wry smile; others may have felt stung by the barbed jibe attributed to an anonymous northern barbarian.

I think it would be good if we could accept the story as true. Some parts of it possibly _are_ true, even if the conversation reported by Dio never happened – or at least not in the way he describes. It is not unrealistic, for example, to imagine Julia Domna visiting the imperial frontierlands in what is now Scotland. She was certainly no stranger to dangerous war-zones. One of her honorific titles was Mater Castrorum, ‘Mother of the Army Camps’, bestowed in recognition of her willingness to accompany her husband on military campaigns. Whether she met the wives of any barbarian leaders on such occasions is debatable, although not implausible. I’m inclined to think we can consider the possibility that she not only visited Scotland 1,800 years ago but had a face-to-face encounter with the wife of a local chieftain. Musing even further, we can perhaps imagine these two high-status women – one a Syrian, the other a Caledonian – exchanging a few words, not directly but through an interpreter. Whatever they said to one another, it is more likely to have consisted of polite greetings rather than the mockery and ‘witty remarks’ placed into their mouths by Cassius Dio.

* * * * *

Epilogue

Julia Domna outlived not only her husband but also their sons, Caracalla and Geta. The brothers became joint emperors following the death of their father in 211 but their relationship was mutually hostile. Within months, Geta was murdered by Caracalla’s soldiers, dying in his mother’s arms. Julia detested Caracalla but relished the power and influence she acquired during his reign and chose to maintain a public image of maternal loyalty. The complicated relationship between mother and son even prompted rumours of incest, but Cassius Dio makes no mention of this and modern historians dismiss it as malicious gossip emanating from the imperial court. Caracalla turned out to be an unpopular emperor and his assassination in 217 came as no surprise, but his death deprived his mother of political status. Julia, by then in her fifties, suddenly found herself at risk of being exiled from Rome and ending her days in obscurity. This bleak prospect filled her with dread, especially as she had begun to nurture ambitions of ruling the Empire herself. She died soon afterwards, allegedly starving herself to death but – according to Dio – finally succumbing to the breast cancer that had afflicted her for many years.

The emperor Caracalla with his mother Julia Domna.

* * * * *

Notes & references

Julia’s second name or ‘cognomen’ Domna derives from an ancient Arabic word meaning Black. It distinguished her from her elder sister Julia Maesa, a woman of ruthless ambition whose own story is no less remarkable.

– – – – –

The conversation between Julia Domna and the Caledonian lady is reported in Book 77, section 16, of Cassius Dio’s Historia Romana.

For this blogpost I used the Loeb Classical Library edition, available online at Lacus Curtius.

Substantial portions of the original text of the Historia Romana have not survived, the lost material being known from an abridged version written by the Byzantine scholar John Xiphilinus in the eleventh century.

– – – – –

Some journal articles I have found useful:

Riccardo Bertolazzi, ‘The depictions of Livia and Julia Domna by Cassius Dio: some observations’ Acta Antiqua Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae vol. 55 (2015), 413-32

Andrew Scott, ‘Cassius Dio’s Julia Domna: character development and narrative function’ Transactions of the American Philological Association vol. 147 (2017), 413-33

Christopher T. Mallan, ‘Cassius Dio on Julia Domna’ Mnemosyne vol. 66 (2013), 734-60

Caillan Davenport, ‘Sexual habits of Caracalla: rumour, gossip and historiography’ Histos vol. 11 (2017), 75-100

Julia Domna and Septimius Severus with their sons Geta and Caracalla (Geta’s face has been deliberately erased).

* * * * * * *