Pictish warriors on an 8th-century sculptured stone at Aberlemno in Angus.

In the eighth century, under the rule of their king Onuist son of Urgust (Óengus mac Fergusa), the Picts became the dominant power in North Britain. Onuist had secured his position as the paramount Pictish king by destroying various rivals during a series of bitter conflicts in the late 720s. Early in the following decade he invaded Dál Riata, the homeland of the Scots, ravaging much of it and bringing the rest under his authority. By 740, the two main kingdoms of Dál Riata, based respectively in Lorn and Kintyre, were effectively his vassals.

From this position of strength, and with formidable military resources at his disposal, Onuist turned his eye southward to the land of the Clyde Britons. These people were ruled by their own kings whose stronghold lay on the summit of Alt Clut, the towering ‘Rock of Clyde’ at Dumbarton (Gaelic Dùn Breatainn, ‘Fortress of the Britons’). To Onuist, the Britons were a rival power whose independence posed an obstacle to his ambitions. so he challenged them to battle. The ensuing clash occurred in 744, at a site whose name is not recorded. We do not know the result: it may have been inconclusive, with neither side claiming victory. Six years later, the two armies met again, but this time the outcome was not in doubt:

‘A battle between Picts and Britons, and in it perished Talorcan, son of Urgust, and his brother; and there slaughter was made of the Picts along with him.’

This information comes from from the Annals of Tigernach, a medieval Irish chronicle. The same battle is mentioned in another Irish source, the Annals of Ulster, where the location is given a name:

‘The battle of Catohic between Picts and Britons, and in it fell Talorcan, son of Urgust, the brother of Onuist.’

The name ‘Catohic’ is obscure and otherwise unknown. It appears in no other source, nor can it be identified on a modern map. The same can be said of the name ‘Ocky’ which appears in a third Irish chronicle, the Annals of Clonmacnoise (see Appendix 3 below). A more intelligible name is provided by Annales Cambriae, the Welsh Annals:

‘A battle between the Picts and the Britons; that is, the battle of Mocetauc, and their king Talorcan was slain by the Britons.’

Also from Wales comes Brut y Tywysogion (‘Chronicle of the Princes’) which has the following entry:

‘In the same year [i.e. 750] was the battle of Mygedawc, where the Britons were victorious over the Pictish Gaels after a bloody battle.’

A different version of Brut y Tywysogion also refers to the battle but, like the Irish chronicles, it names the Pictish commander:

‘750 years was the age of Christ when there was a battle between the Britons and the Picts, in the field of Maesydawc. And the Britons slew Talorcan, king of the Picts.’

Mocetauc and Mygedawc are variant spellings of the same name. Their pronunciation is similar: in both, the consonants are pronounced ‘hard’, i.e. c has the sound of k (not s) and g is not softened to j. Maesydawc seems to be a different name, although it shares a similar ending with Mocetauc and Mygedawc and might be related to them in some way.

Our final piece of information comes from the Annals of Tigernach which report a death under the year 752:

‘Teudubur, Beli’s son, king of Alt Clut [died].’

This king is also named in a medieval Welsh genealogy or ‘pedigree’ of the kings of Alt Clut. He seems to have ruled the Britons for thirty years, from 722 to 752, and is probably the man to whom the great victory of 750 should be credited. There is some doubt as to whether he really did die in 752, with some historians wondering if the Irish annalists noted his death a couple of years too late. The Welsh Annals assert that he died in 750 and it is possible that this is correct.

Taken together, then, the Irish and Welsh sources tell us that a major battle was fought in 750, at Mocetauc or Mygedawc, a place which may also have been called Maesydawc, ‘Catohic’ or ‘Ocky’. It was a massive setback for the Pictish king Onuist, whose own brother Talorcan fell among the casualties. The victor was most likely Teudubur, king of Dumbarton, who died later in the same year or in 752. In Pictland, the defeat seems to have had major repercussions, for the Annals of Ulster tell us that the year 750 marked ‘the ebbing of the sovereignty of Onuist’. Maybe his rivals at home perceived that he was not invincible and began to stir against him? The Britons, by contrast, would have celebrated one of the greatest military successes in their history. They had thwarted the ambitions of the mighty Onuist. They had slain his brother Talorcan, a seasoned commander who had played a key role in the Pictish conquest of Dál Riata. The importance of the battle is therefore not in doubt. But where was it fought?

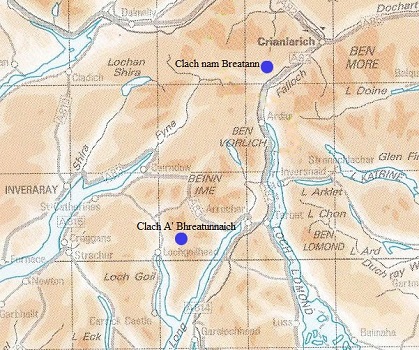

North Britain in 750.

Location

In the late nineteenth century, the Scottish historian William Forbes Skene identified Mocetauc/Mygedawc as Mugdock in Strathblane, the valley of the Blane Water. This was a logical deduction and is now generally accepted by place-name experts. At the time of the battle, Strathblane was an area where Cumbric – a language closely related to Welsh – was the everyday speech of the inhabitants. Cumbric was the language of the Clyde Britons, whose kings almost certainly held authority in Strathblane from their stronghold at Dumbarton. It is likely that Mugdock is a name of Cumbric origin, a relic of the period when many places around the Clyde had ‘Welsh-sounding’ names.

Skene was a leading figure in Scottish antiquarian circles and his influence is still felt today. His identification of Mugdock as the site of a famous Dark Age battle seems to have prompted his contemporary John Guthrie Smith, a resident of the Strathblane valley, to pinpoint the location more closely. In his book The Parish of Strathblane, published in 1886, Smith connected the battle with various local sites. He called the Britons ‘Cymry’ (pronounced Cum-ree), a term still in use today among native-speakers of Welsh. It means ‘compatriots’ or ‘fellow countrymen’. The northern equivalent was Cumbri, hence Smith’s use of Cumbria as a name for the land of the Clyde Britons. In the following passage, he offers a detailed account of the battle of Mocetauc:

“The field of this battle can be traced with but little difficulty. The Cymric army was posted on the high ground on Craigallian – then part of Mugdock – above and to the east and west of the Pillar Craig, with outposts stationed on the lower plateau to the north, and there awaited the Picts, who came up Strathblane valley through Killearn from the north on their way to the interior of Cumbria. Near the top of the Cult Brae, in a line with the Pillar Craig, there is a rock still called Catcraig, i.e., Cadcraig, meaning the “Battle Rock,” and in their efforts to dislodge the Cymric army, whom they could not leave in their rear to fall upon them when they had passed, the Picts doubtless had penetrated thus far and here the battle began. It was continued all over Blair or Blairs Hill, i.e., the “Hill of Battle” – the rising ground on Carbeth Guthrie which commands the valley of the Blane – and Allereoch or Alreoch, i.e., the “King’s Rock,” was certainly so named from being the place where King Talargan fell when the defeated Picts were being driven back to the north-west. The standing stones to the south-east of Dumgoyach probably mark the burial place of Cymric or Pictish warriors who fell in the bloody battle of Mugdock.” [Smith, Parish of Strathblane, p.8].

This romantic reconstruction owes more to Victorian imagination than to eighth-century history. Nevertheless, some parts of it can be accepted as broadly accurate. The Pictish army probably did come down from the north before marching south along the valley of the Blane Water, and the Britons may indeed have relied on lookouts or ‘outposts’ for news of the enemy’s advance. But the rock Catcraig is unlikely to commemorate this battle or any other, despite Smith’s belief that the name is significant (cat or cad is a common word for ‘battle’ in both Gaelic and Cumbric). There are, in fact, many Catcraigs in Scotland but most – if not all – have a name meaning simply ‘rock of the wildcat’. Blair Hill or Blairs Hill likewise has a first element formed from Gaelic blar (‘field’ or ‘plain’), another common element in Scottish place-names. Although blar occasionally appears in the context ‘field of battle’ this is not its primary meaning and it generally appears without any military connotation. The supposed ‘King’s Rock’ at Alreoch is more likely to be ‘speckled rock’ (from Gaelic riabhach) and, although the standing stones of Duntreath near Dumgoyach are undoubtedly ancient, there is no reason to associate them with an early medieval war-grave. Their origin lies much further back, in prehistoric times.

The simple truth is that we cannot reconstruct the progress of the battle of Mugdock in any great detail. We cannot even be sure that it was fought near the present-day Mugdock hamlet rather than elsewhere in Strathblane – the name ‘Mugdock’ was formerly attached to a medieval barony encompassing much of the valley. In cases such as this, where precise geographical details are unknown, it is often tempting to look for suggestive clues in minor place-names. This was the strategy chosen by John Guthrie Smith but it didn’t bring much clarity to the picture and merely threw up a few red herrings. A more objective approach is to step back from the local maps to consider the battle of 750 in its broader geographical and political contexts.

Alt Clut, the Rock of Clyde at Dumbarton, Fortress of the Britons (Photo © B Keeling).

Allies and enemies

In 2009, the Canadian historian James E. Fraser discussed the significance of the battle of Mugdock in his book From Caledonia to Pictland. Fraser believed that the Pictish defeat and the subsequent ebbing of Onuist’s power ‘probably shook northern Britain’. He also suggested that the Clyde Britons may have regarded their victory as comparable to the famous defeat of an invading English army by the Picts at Dun Nechtain in 685. Both battles, as Fraser observes, seem to have thwarted ‘the imperial designs of a neighbouring superpower’. We should therefore be in no doubt that the clash at Mugdock was one of the most important battles in the history of early medieval Britain.

Fraser suggested that the battle should be seen not in isolation but as part of a much wider picture of wars and alliances. Ten years earlier, in 740, Onuist had previously come into conflict with Northumbria, the powerful English kingdom beyond his southeastern border. Contemporary English sources claim that he had an alliance with Mercia, Northumbria’s traditional enemy in the English midlands, and that the Mercians invaded Northumbria from the south in the same year. During the 740s, Onuist managed to settle his differences with the Northumbrian king Eadberht and, by the end of the decade, the two had become allies. They had much in common: both were men of ambition, keen to expand their respective realms; both faced a serious obstacle to their expansion – the kingdom of the Clyde Britons. In 750, Eadberht marched west into what is now Ayrshire, seizing the plain of Kyle together with ‘other districts’. These lands were almost certainly taken from Britons, perhaps from subordinates of the king of Alt Clut. One key question is whether the conquest of Kyle occurred before or after the battle of Mugdock. Before is surely more likely, for Eadberht may have been less keen to menace the fringes of a kingdom whose army had recently smashed the fearsome Pictish war-machine. This would be consistent with Northumbria’s apparent neutrality when Talorcan moved against the Britons: Eadberht probably thought the Picts fully capable of rampaging all the way down Strathblane to threaten Dumbarton itself. If he had foreseen that his allies would fail so spectacularly, he might have been tempted to bring his own forces into Clydesdale from the south, to boost Talorcan’s chance of victory.

Places connected with the Battle of Mugdock, superimposed on a modern map.

The road to war

Turning now to the circumstances of the battle, we can make a few observations about its logistical aspects: the routes of approach to the battlefield and how long each army took to get there. There can be little doubt that the Picts entered Strathblane from the north. As John Guthrie Smith envisaged, they probably came via Killearn. This village stands on an old route running from Dumbarton to the ancient Fords of Frew, a crossing-point on the River Forth still used by armies as late as 1745. It is likely that Talorcan and his warriors, marching south from their Perthshire heartlands, crossed at Frew before turning southwest towards Killearn. The Pictish army would have been a mixture of horsemen and foot-soldiers, all travelling at an average rate of no more than 25 miles per day. The terrain would not have been easy, for there were no long stretches of well-maintained highway. Moreover, this was long before the extensive wetlands of the Forth Valley were drained and reduced. Progress across the treacherous mosses would have been slow for man and beast alike. The distance from Strathearn, a plausible mustering-point for Talorcan’s army, to the area around Mugdock is roughly 30 miles. This probably meant a 2-day journey for the Picts, even if they maintained a steady march-rate of 15 miles per day, with essential rest-periods for horses. After crossing the Fords of Frew they probably came into lands that acknowledged Teudubur as king. Here, the invaders no doubt began to ravage the countryside by burning farmhouses and terrorising the people, before making camp as evening fell. Meanwhile, news of the onslaught would have been sent to Alt Clut by the swiftest means, prompting Teudubur to respond by mustering his own forces quickly. He may even have been expecting an attack, or it may have come without warning.

The Britons had a shorter and less arduous trek to the battlefield. From their fortress at Dumbarton, they would have gone via Duntocher and Milngavie to enter the Strathblane valley, picking up the route of today’s A81 highway. The entire distance from Dumbarton to Mugdock hamlet was only 10 miles, a distance easily completed within a half-day’s march. The Britons probably reached the middle of the valley some hours before the enemy. This would have allowed them enough time to choose the battlefield and to post lookouts – the ‘outposts’ imagined by Smith. The ensuing contest would have been brief and bloody, a horribly gruesome spectacle involving a tangled mass of foot-soldiers hacking and stabbing amid a clamour of yells and screams. Cavalry did not necessarily play a major role, even if some warriors rode to the battlefield. Although we see carvings of armed horsemen on Pictish stones, there is no strong evidence that mounted combat was a regular feature of warfare in eighth-century Britain. The battle of Mugdock is more likely to have been a fight between two infantry armies. At some point, after a few hours of relentless carnage, the Picts broke and fled. Few would have escaped the field alive; fewer still would have come home to the farmlands of Perthshire.

Mugdock Castle (from J.G. Smith’s Parish of Strathblane)

Aftermath

Teudubur’s great victory enabled his people to avoid the fate of their Scottish neighbours: Dál Riata seems to have remained under Pictish overlordship until the middle of the ninth century, when Viking raids disrupted the status quo, but the Clyde Britons appear to have remained independent. This is remarkable when we consider that they endured another Pictish invasion six years after their triumph at Mugdock. The aggressor was again Onuist, but this time he was taking no chances. Not only did he command the army himself, he co-ordinated the attack with his English ally Eadberht who simultaneously led a Northumbrian force into Clydesdale. Faced with overwhelming odds, the king of the Britons – Teudubur’s son Dyfnwal – surrendered at Dumbarton on 1st August 756. This was a war Dyfnwal could not hope to win. However, there is no hint that his capitulation heralded a long period of subjugation to Pictish or English overlords. Eadberht tasted the fruits of victory for a mere nine days: on 10th August, his army was butchered in a sudden ambush as it marched home from Govan on the south bank of the Clyde. Some historians think the unidentified attackers were vengeful Britons, others think the Picts were responsible. Onuist himself returned home safely, laden with plunder, but he had fought his last campaign. We hear no more of him until his death in 761. His successors maintained the Pictish overlordship of Dál Riata but there is no evidence that the kings of Alt Clut were similarly reduced as vassals. Not until the eleventh century, when the Picts and Scots were united in the powerful new kingdom of Alba, did Teudubur’s descendants finally relinquish their independence.

This image of the Israelite king David on the 8th-century St Andrews Sarcophagus may be a contemporary likeness of Onuist, king of the Picts (Photo © B Keeling).

* * *

Appendix 1: Dineiddwg

In the early twentieth century, a large mansion was built at Mugdock for the wealthy Glasgow baker William Beattie. It was given the name ‘Dineiddwg’ because this was commonly assumed to be the ancient name of Mugdock. The assumption was actually not much older than the mansion itself, having arisen from a footnote in one of W.F. Skene’s books, The Four Ancient Books of Wales, published in 1868. Skene drew attention to a medieval Welsh poem attributed to the bard Taliesin who allegedly lived in North Britain in the sixth century. The poem ends with the following lines:

Rwg kaer rian a chaer rywc

rwg dineidyn. a dineidwc

eglur dremynt a wyl golwc.

Rac rynawt tan dychyfrwymwc.

an ren duw an ry amwc.

(‘Between Caer Rian and Caer Rywg,

between Dineiddyn and Dineiddwg;

a clear glance and a watchful sight.

From the agitation of fire, smoke will be raised,

and God our Creator will defend us.’)

The poem in question was composed long after the sixth century by an anonymous Welsh poet who was not Taliesin. It is allusive rather than narrative, with obscure references to nature and magic. The final lines, however, include a mention of Dineiddyn, the ancient Welsh name for Edinburgh. This led Skene to believe that the other three places – Caer Rian, Caer Rywg and Dineiddwg – were also in North Britain. Din is an old Welsh word meaning ‘fortress’, hence Edinburgh is ‘Fortress of Eiddyn’. Dineiddwg is presumably ‘Fortress of Eiddwg’ but the second element is difficult to identify. Skene wondered if it might be echoed in the names Mocetauc, Mygedawc and Maesydawc, with Dineiddwg being yet another alternative name for Mugdock. This was only a guess, but it was enough to encourage John Guthrie Smith to go even further: ‘Dineiddwg means therefore the Fort of Eiddwg or Edawc, who may have been a Cymric chief, with his castle Dineiddwg or Dinedawc standing in a commanding position on his estate Maeseiddwg or Maesedawc’. Here, Smith was simply using his imagination to create a dramatic picture out of virtually nothing. Needless to say, his 1886 book is almost certainly where William Beattie found a suitably eye-catching name for a new mansion at Mugdock.

—

Appendix 2: Folklore

I visited Mugdock Country Park a few years ago but didn’t have much time to explore the surrounding area. Since my visit I have learned that a sign at the nature reserve beside Loch Ardinning tells of a Dark Age battle fought in the vicinity. The sign dates this battle to 570 AD and associates it with the famous King Arthur. John Guthrie Smith knew of the tradition and connected it with a curious discovery in 1861 when railway workmen unearthed ‘an immense deposit of human and horse bones’ nearby. He also drew attention to a boulder known as Arthur’s Stone on a hillside near Craigbarnet, slightly northwest of Mugdock. I’m no great believer in the idea of a historical figure behind the Arthur legends and rarely mention the topic on this blog. The legends were, of course, widely popular in the Middle Ages and many places in Britain enthusiastically claim an Arthurian connection. At Mugdock, however, we find the curious coincidence of an alleged Arthurian battle near the site of a genuine historical one. At first glance, it is tempting to wonder if the two are connected, with the legendary King Arthur being grafted onto local traditions of the great battle of 750. Unfortunately, the possibility that a folk-memory of the Pictish defeat survived among the people of Strathblane is very remote. The area was caught up in the upheavals of the eleventh and twelfth centuries, which saw a southward expansion of the kingdom of Alba. By 1070, the land of the Clyde Britons had been conquered and absorbed. One effect of the conquest was the introduction of Gaelic speech and a new sense of ‘Scottishness’, leading to the demise of the old Cumbric language and the cultural identity it represented. Many indigenous traditions faded away and, within a few generations, the Clyde Britons had become Gaelic-speaking Scots. Almost everything of their former history was soon forgotten, including tales of heroic kings and ancient wars. By the end of the twelfth century, it is unlikely that anyone in Mugdock knew that a once-famous battle had been fought there.

—

Appendix 3: Primary sources

The original entries from the medieval chronicles mentioned at the start of this blogpost are listed below. Most of these texts were written in Latin, with two exceptions: Brut y Tywysogion (in Welsh) and the Annals of Clonmacnoise (a translation in seventeenth-century English).

Annals of Tigernach

750 – Cath eter Pictones et Britones, i testa Tolargan mac Fergusa & a brathair, & ár Picardach imaille friss.

752 – Taudar mac Bile, rí Alo Cluaide.

Annals of Ulster

750 – Bellum Catohic inter Pictones & Brittones in quo cecidit Talorggan mc. Forggussa, frater Oengussa.

Annals of Clonmacnoise (misdated the battle by 4 years)

746 – The battle of Ocky between the Picts & Brittans was fought where Talorgan mcffergus, brother of K. Enos, was slaine.

Annales Cambriae or ‘Welsh Annals’

750 – Bellum inter Pictos & Brittones, id est gueith Mocetauc. Et rex eorum Talargan a Brittonibus occiditur. Teudubur filius Beli moritur.

Brut y Tywysogion (‘Red Book of Hergest’ version)

Deg mlyned a deugeint a seith cant oed oet Crist pan vu y vrwydyr rwg y Brytanyeit ar Picteit yg gweith Maesydawc ac y lladawd y Brytanyeit Talargan brenhin y Picteit.

* * * * *

Notes & references

I was inspired to write this blogpost after conversations on Twitter with Debra Torrance of Milngavie.

Indigenous Archaeology in and around Milngavie is a local heritage group whose interests cover the Mugdock area. Take a look at their Facebook page.

John Guthrie Smith, The parish of Strathblane and its inhabitants from early times : a chapter in Lennox history (Glasgow, 1886)

James E. Fraser, From Caledonia to Pictland: Scotland to 795 (Edinburgh, 2009)

W.F. Skene’s note on Dineiddwg appears on page 401 in Vol.2 of his book The Four Ancient Books of Wales (Edinburgh, 1868).

I mention the battle of Mugdock in my books The Men of the North: the Britons of Southern Scotland and The Picts: a history.

James Johnston in his 1904 book The Place-Names of Stirlingshire suggested (at page 54) that the name Mugdock is of Gaelic origin: mag-a-dabhoich, ‘plain of ploughed land’. But it is more likely to be a pre-Gaelic, Cumbric name, as both W.F. Skene and John Guthrie Smith implied in their notes on Dineiddwg.

The name ‘Catohic’ from the Annals of Ulster is very obscure. I have been unable to find any information on it. The same can be said of ‘Ocky’ in the Annals of Clonmacnoise. Both might be scribal errors due to miscopying of the original names.

A description of the Duntreath standing stones can be found on the Canmore database.

* * * * * * *

This post is part of the Kingdom of Strathclyde series:

* * * * * * *