Gordon Noble and Nicholas Evans, The King in the North: the Pictish Realms of Fortriu and Ce. Birlinn: Edinburgh, 2019, xiv +209 pp. £14.99 pbk. ISBN 978 1 78027 551 2

Much progress has been made in the past 30 years to bring the Picts into the mainstream of early medieval European history, yet they are still often regarded as enigmatic and puzzling. This is perhaps understandable, given that – for many people – the most vivid evidence of the Pictish contribution to Scotland’s past is a unique set of mysterious symbols carved on standing stones. Any book that attempts to de-mystify the Picts is therefore timely and welcome. In this case, the reader is presented with a volume of what are essentially separate academic essays, the majority previously published in scholarly journals or monographs but here updated and newly edited. All are linked by a shared focus on northern Pictland, an area generally understood as lying north of the Grampian Mountains and encompassing Aberdeenshire, Moray, Inverness-shire and Easter Ross. The essays are linked by authorship, having been produced by scholars involved in the Northern Picts project at the University of Aberdeen. Like the project itself, the volume is interdisciplinary, covering a range of archaeological and historical topics.

One of the book’s stated objectives is to highlight the importance of northern Pictland and, in so doing, to redress the balance between this area and its southern counterpart. It is certainly true that historians and archaeologists have traditionally placed a focus on southern Pictland, roughly the area between the Grampians and the Forth-Clyde isthmus. In addition to being the core of the later kingdom of Alba, southern Pictland was until recently assumed to include Fortriu, a powerful kingdom whose rulers wielded overkingship over a large swathe of Pictish territory. Northern Pictland, by contrast, was long regarded by scholars as something of a backwater, in spite of its containing some of the most impressive examples of Pictish sculpture. These old perceptions of political geography shifted dramatically in 2006 with the publication of Alex Woolf’s proposal that Fortriu should be seen as a northern realm centred on lands around the Moray Firth. Widespread acceptance of Woolf’s argument encouraged historians and archaeologists to direct more attention to the area north of the Grampians and, in 2012, the Northern Picts project was established. An exciting programme of archaeological surveys and excavations at key sites north of the Grampians has continued in the ensuing years, with analysis and interpretation of the data being presented in this collected volume.

The main contents comprise eight chapters, of which seven are edited versions of previously published studies while the eighth was written specially for this book. A shorter final chapter, giving a summary and overview, is followed by a list of places to visit and an extensive, up-to-date bibliography. Looking at the chapters in sequence, the first sees the archaeologist Gordon Noble introducing a number of key themes: the geographical extent of northern Pictland; the impact of Woolf’s 2006 paper; the subsequent recognition of Fortriu and another kingdom – called Ce – as the main northern Pictish polities; and the work of the Northern Picts project. In Chapter Two, historian Nicholas Evans discusses the surviving primary source material relating to northern Pictland, noting the difficulties presented by the texts and the care that should be exercised when trying to interpret them. Far too much trust has indeed been placed in their testimony, which until quite recently was often accepted at face value. As Evans observes, it is essential that the contexts in which these sources were written are acknowledged, especially those texts produced long after the end of the Pictish period by authors for whom the past was something to be adapted and repackaged. Evans also examines the rise to prominence of the kings of Fortriu, their association with Pictish overkingship and the eventual disappearance not only of the name of their kingdom but of Pictish identity as a whole.

Chapter Three diverts our attention from textual to archaeological evidence with Gordon Noble’s study of fortified settlements in northern Pictland. Noble discusses sites such as the massive coastal promontory fort at Burghead – the largest Pictish fortress so far known – and the multiple enclosure hillfort of Mither Tap, Bennachie, together with less imposing enclosed settlements like the one recently identified at Rhynie. A broader context is the emergence of fortified settlements across early medieval northern Britain as places where elites exercised and displayed their authority, hence the association of hillforts – including a couple of Pictish ones – with contemporary references to kingship and royal warfare. In Chapter Four we are offered a more detailed look at the ‘enclosure complex’ at Rhynie, a fascinating location where excavations by the Northern Picts project have enabled archaeologists to identify a landscape of power and ritual. Evidence of metalworking and jewelsmithing, together with shards of imported Mediterranean pottery, confirm this site’s high status. This new data also provides a context for two unusual and well-known sculptured monoliths – the Craw Stane with its Pictish symbols and ‘Rhynie Man’ with its fierce-looking, axe-wielding human figure.

The archaeological theme continues in Chapter Five, where cemeteries and single graves provide evidence for the burial practices of northern Pictland. Across the region, evidence from aerial survey and excavation suggests a burial tradition involving square or circular barrows, with an apparent absence of the stone-lined ‘long cist’ graves observed south of the Grampians. Interestingly, some barrows were made bigger or more elaborate as time went by, implying that successive generations of the living community deliberately altered the appearance of graves for reasons of their own, perhaps to support claims of authority or ancestry or to retrospectively enhance the status of the dead. Also in this chapter we see how new interpretations of archaeological data are changing older perceptions of Pictish society, namely the important observation that Pictish symbol stones do not – after all – appear to have a strong association with Pictish graves.

Chapter Six describes the hoard discovered in 1838 at Gaulcross – a collection of Late Roman hacksilver buried near two ruined stone circles in an Aberdeenshire field. The hoard is likely to have been deposited in the fifth, sixth or seventh century. Almost all of the original collection of finds subsequently disappeared. However, a new programme of surveying and metal detecting in 2013 unearthed more than 100 additional items, enabling the Gaulcross hoard to be studied alongside two more – one from Traprain Law in East Lothian and another from Norrie’s Law in Fife – these three being the only known hoards of pre-Viking hacksilver from Scotland. Possible contexts for their acquisition and deposition are here usefully considered by analogy with similar hoards from elsewhere in Europe, notably from Denmark. A plausible theory is that the Gaulcross hoard may have been ritually interred by members of a local Pictish elite eager to link themselves to an ancestral or sacred aura represented by the ancient stone circles.

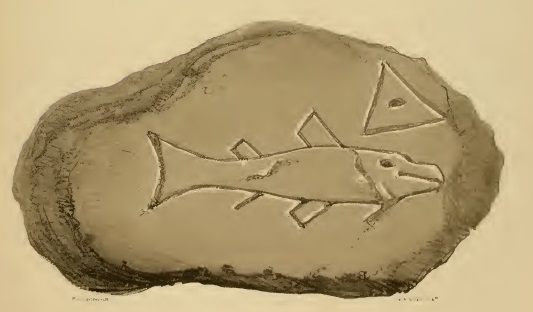

Moving on to the book’s seventh chapter we encounter the Pictish symbol system, undoubtedly the most familiar and most controversial topic addressed in this volume. A vigorous debate over the question of what message the symbols were intended to convey has been running for more than 100 years and shows no sign of abating. Among a plethora of theories some are more plausible than others, with the idea that the symbols might represent a form of writing being one of the front-runners. This particular theory is here described as the current academic consensus. It certainly draws support from comparisons with the ogham of Ireland and western Britain and the runes of Scandinavia and northern Germany. The runic script and ogham are now thought to have emerged in the second and fourth centuries AD respectively, each being a form of ‘barbarian’ experimentation with writing on the fringes of the Roman Empire. Inspired by the Roman alphabet, although not devised in imitation of it, both ogham and runes may have enabled ambitious elites to publicly communicate their power and status, in the same way that Latin inscriptions conveyed Roman prestige. Here the argument goes on to propose that, if Pictish symbols did indeed originate as early as ogham or Scandinavian runes, they were probably used by high-status families to reinforce social positions. This explanation offers a plausible context for the stone plaques inscribed with simple symbol designs at the sea-stack of Dunnicaer on the Aberdeenshire coast. Fieldwork on this near-inaccessible site was undertaken by the Northern Picts project from 2015 to 2017 and confirmed an older theory that the site had been a Pictish fort. A stone rampart in which the plaques had been set and displayed has yielded a construction date between the late third and mid-fourth centuries AD. If the symbols were inscribed at the same time, the origin of the system is pushed back by several hundred years from its traditional start-date in the sixth or seventh century. As the authors of Chapter Seven point out, it might be no coincidence that such an early date for the origin of the symbols corresponds with the first appearance of the term Picti in contemporary Roman texts. The possibility that the symbols, with their remarkable consistency of form, were devised simultaneously with the forging of a new ‘Pictish’ identity in the far northern regions of Britain is certainly a thought-provoking notion to add to the age-old debate.

Fish symbol and triangle on a stone from Dunnicaer.

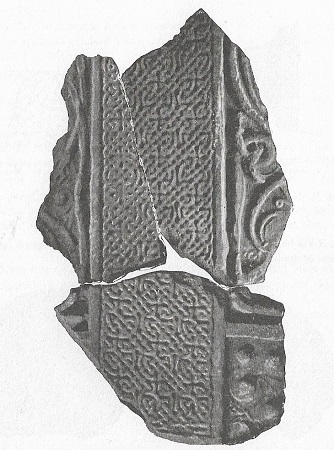

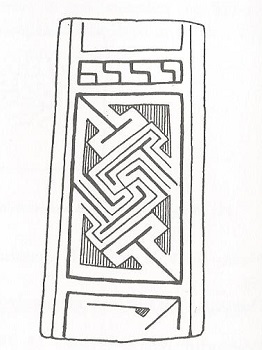

Chapter Eight, the last of the main essays, has been newly written for the book. It looks at the transition from paganism to Christianity in northern Pictland, a process barely visible in the surviving sources. A lack of authentic information on what Pictish paganism actually looked like has allowed fanciful modern ideas about ‘Celtic’ religious beliefs to fill the gaps. The few genuine contemporary references of direct relevance to the topic were, to compound the difficulties, written not by pagan Picts but by non-Pictish Christians keen to highlight the superiority of their own religion. For a more objective view of Pictish paganism we turn once again to archaeological evidence and to the inferences that can be drawn from it. Thus, at the Sculptor’s Cave at Covesea in Moray, recent work suggests that the place was a ritual venue where human sacrifice was performed in the third to fourth centuries AD. Similarly, one interpretation of the Rhynie Man carved figure is that his axe-hammer was not a weapon of war but a tool for the ritual slaughter of cattle. Dating the pagan-to-Christian transition in northern Pictland is no easy task but the texts imply that the process began in the sixth century and was virtually complete before the end of the seventh. By 697, a bishop called Curetán appears to have been based at Rosemarkie in Easter Ross, perhaps serving the northern Pictish territories while a more southerly counterpart held a separate bishopric on the other side of the Grampians. Also in Easter Ross lies the monastic site of Portmahomack, the focus of extensive modern excavations that have confirmed its importance during the fifth to eighth centuries AD. A number of smaller ecclesiastical sites identified by the Northern Picts project as potentially significant await investigation in the future. The chapter reminds us that there remain many unanswered questions, such as to what extent northern Pictland was evangelised by missionaries from St Columba’s monastery on Iona – as claimed by Bede – rather than by a more diverse range of personnel.

In the closing chapter, Gordon Noble observes that ‘we have gone from a lack of identified and dated Pictish sites in northern Pictland to one of the best dated sequences from early medieval Scotland’. It is a credit to the work of all those involved in the Northern Picts project that such an observation can now be made. This collection of essays, available in paperback, brings the project’s detailed findings to a wider audience than before, giving the general reader easy access to an important corpus of specialised research. For scholars of Pictish history and archaeology, it provides a useful compendium of data and analysis on a number of current topics. It is an excellent book and I have no hesitation in recommending it.

* * * * * * *