Modern sculpture of King Arthur on the summit of Tintagel Island.

Although this blogpost briefly mentions Scotland it is mainly about the far south-west corner of England. It does however deal with the early medieval period and with another of the ‘Celtic’ regions of Britain. It is one of a number of non-Scottish posts that occasionally appear here at Senchus.

* * *

A holiday on the north coast of Cornwall last year gave me an opportunity to visit a couple of places associated with King Arthur. One was Tintagel Castle, a strikingly impressive site that I was lucky enough to explore on a warm, cloudless day. The other was Slaughterbridge, a Cornish candidate for Camlann – the site of Arthur’s final battle where both he and his treacherous nephew Mordred were said to have perished.

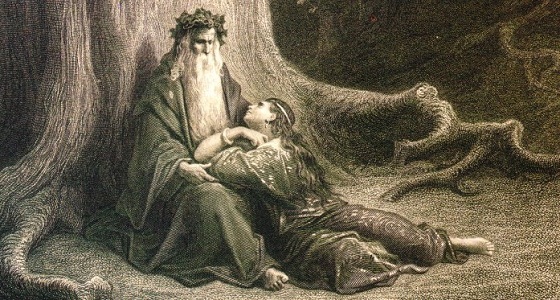

Arthur and Mordred in combat at Camlann, painted by William Hatherell (1855-1928)

The question of whether or not the Arthurian legend preserves the authentic story of a sixth-century warlord called Arthur/Artorius is, of course, a matter of debate. My own thoughts on this controversial topic appeared most recently as a chapter in Scotland’s Merlin, published by Birlinn Books in 2016. For the record, I currently favour south-west Scotland as a possible source of the Arthurian legend’s original core, but this does not necessarily mean that I see Arthur himself as any more ‘real’ than Batman. Maybe Arthur existed, maybe he didn’t. The question is not, in any case, a crucial one for historians of early medieval Britain. Hence, Arthur’s story is frequently absent from modern textbooks on the period, including my own study of the Britons of southern Scotland (The Men Of The North, published in 2010). I nevertheless retain an interest in Arthur’s legend – and Merlin’s too – especially at places with tangible ‘Dark Age’ connections. In Cornwall, both Tintagel and Slaughterbridge fall into this category, each of them being sites where objects from the sixth century – the time when Arthur supposedly existed – can still be seen today.

Old engraving of Tintagel Island and the castle ruins.

Tintagel

The island of rock now crowned by Tintagel’s medieval castle formerly supported a substantial high-status settlement occupied in the ‘Arthurian’ era of the fifth and sixth centuries AD. Archaeological excavations have unearthed artefacts and structures from this period, ranging from pottery and glassware to traces of buildings. The pottery includes large jars (amphorae) that once contained wine imported from Mediterranean lands. These show that Tintagel’s inhabitants were involved in long-distance trading networks with other parts of what had once been the Western Roman Empire. Plenty of information about the archaeological finds is available online and I have included a couple of links at the end of this blogpost.

For many visitors, what attracts them to Tintagel Castle is its claim to be the place where Arthur was conceived. The claim derives from the twelfth century when Geoffrey of Monmouth’s History of the Kings of Britain described how Arthur’s father, King Uther Pendragon, used deception to satisfy his lust for Lady Igraine, the beautiful wife of Duke Gorlois of Cornwall. A potion concocted by Merlin enabled Uther to disguise himself as Igraine’s husband so that he could spend the night with her in the Duke’s stronghold at Tintagel. The offspring of this deceitful liaison was Arthur, who eventually succeeded to Uther’s throne.

Whatever our opinions on Geoffrey of Monmouth’s value as a source of early British history, there is no doubt that he knew how to tell a good tale. His dramatic account of Uther and Igraine ensured that Tintagel would forever have a place in Arthurian lore. Needless to say, the teams of archaeologists who have excavated there (most recently in 2018) have found no trace of Geoffrey’s characters – despite the discovery in 1998 of a stone inscribed with the suggestive name Artognou. Yet the popular belief that this was a place well-known to Arthur and Uther 1500 years ago is still alive in the popular imagination.

The following photographs give an idea of what the modern visitor to Tintagel Castle can expect to see.

Looking back from the castle ruins on the summit of Tintagel Island to the adjacent mainland.

Looking along the coast of North Cornwall from the ruins of Tintagel Castle.

The outlined shape of a rectangular building from the 5th/6th century settlement.

Information board for a group of excavated ‘Dark Age’ buildings.

A pair of early medieval buildings nestling on the slope below the summit.

Looking down from the castle to a small cove and beach.

In the cliffs below the castle lies Merlin’s Cave (the cave on the left).

Slaughterbridge

According to the ancient chronicle known as Annales Cambriae (‘Welsh Annals’), the year 537 witnessed the bloody battle of Camlann in which Arthur and Mordred were slain. The antiquity of this information is uncertain and cannot, on present evidence, be shown to pre-date the tenth century when the Welsh Annals were compiled. Two hundred years later, in the 1130s, Geoffrey of Monmouth placed Camlann in Cornwall, on the River Camel. Cornish tradition has long located the battlefield at Slaughterbridge near Camelford, some 4 miles south-east of Tintagel. Another candidate for Camlann is the Roman fort of Camboglanna (now Castlesteads) on Hadrian’s Wall. Camboglanna is a Celtic name borrowed by the Romans. It means ‘crooked valley’ in the old language of the Britons and could have become Camlann in medieval Welsh. However, there were no doubt many crooked valleys in Roman Britain, so the name Camboglanna might have been a common one. It is also possible that Camlann derives from a different name such as Cambolanda (‘crooked enclosure’).

At Slaughterbridge there is a fascinating visitor attraction called The Arthurian Centre which tells of the local Camlann tradition. The Centre has a tearoom, gift shop and plenty of information on Arthur, as well as a walking trail over part of the presumed battlefield beside the River Camel. The trail meanders through pleasant woodland and ends at a viewing platform above the river. Below the platform, and close to the water’s edge, lies a remarkable Early Christian gravestone from the sixth century. It is carved with a Latin inscription: LATINI IC IACIT FILIUS MA[…]RI (‘Here lies Latinus, the son of M…..’)

Along one edge of the stone runs another inscription, in the ancient Ogham script of Ireland. Although badly weathered, this has been interpreted by at least one expert as possibly containing the same name Latinus. Unfortunately, we have no idea who Latinus was. He may have been a local Briton, or perhaps an Irishman. Whatever his origins, he was clearly a person of sufficient importance to be commemorated in this way. It is interesting to note that the name also appears on another sixth-century memorial, the famous Latinus Stone from Whithorn in south-west Scotland, which marked the grave of a father and daughter.

Unsurprisingly, given the local connection with Arthurian legend, the Cornish Latinus stone has been seen in some quarters as a relic of the battle of Camlann. A separate belief associates it with a battle fought in 825 at a place called Gafulford, where the Britons of Cornwall clashed with the neighbouring West Saxons. Gafulford is thought by some historians to mean ‘Camel-ford’, but others interpret the name differently and place the battle elsewhere. The simple truth is that neither Camlann nor the ninth-century battle can be placed with certainty in the valley of the River Camel, or indeed in Cornwall.

During my visit I was saddened to learn that the inscribed stone is at risk of being harmed by floods. In fact, it has been placed on the At Risk Register, which is a matter of concern. We can only hope that this important monument will soon be protected, perhaps by standing it upright (as it formerly was) and moving it higher up the riverbank (which may have been its original position). Some kind of intervention certainly needs to happen before it is overwhelmed by the river.

The trail from the Arthurian Centre, looking towards the supposed battlefield of Camlann.

The sixth-century inscribed stone lying beside the River Camel.

The Latin inscription.

Information board on the viewing platform.

* * * * *

Notes and Links

The images in this blogpost are copyright © B. Keeling.

Readers may be interested in an article by Professor Andrew Breeze: ‘The Battle of Camlan and Camelford, Cornwall’ Arthuriana 15.3 (Fall 2005): 75-90

The Arthurian Centre has a website and a Facebook page

The Tintagel Dig on Twitter

Information on Tintagel Castle at the English Heritage website

* * * * * * *