Saint Columba, founder and first abbot of the monastery on Iona, died in AD 597. A hundred years or so after his death, a hagiographical Vita or ‘Life’ was written by Adomnán, the ninth abbot of Iona. Among many tales related by Adomnán is the story of Erc moccu Druidi, an inhabitant of the island of Coll, who came to Columba’s attention for all the wrong reasons.

The tale begins when Columba informs two of his monks that ‘a thief called Erc’ has turned up on Mull, on the shore directly opposite Iona. With only a narrow strait separating the two islands, Erc is rather too close for comfort. More than that, he is plainly up to no good, as Columba explains:

“He arrived from Coll last night, alone and in secret, and has made himself a hiding place under his upturned boat, which he has camouflaged with grass. Here he tries to conceal himself all day so that by night he can sail across to the little island that is the breeding-place of the seals we reckon as our own. His plan is to kill them, to fill his boat with what does not belong to him and take it away to his home. He is a greedy thief.”

Columba ordered the two monks to bring Erc to him. Taking a boat across the strait, they sailed over to the Ross of Mull and located the thief, whom they escorted back to Iona. Erc was brought before Columba, who gave him a stern rebuke:

“To what end,” said the saint, “do you persistently offend against the Lord’s commandment and steal what belongs to others? If you are in need, and come to us, you will receive the necessities you request.”

As a gesture of goodwill, Columba offered some freshly slaughtered sheep as compensation for the seals Erc would otherwise have stolen. What happened next is not reported by Adomnán, but Columba presumably told Erc to return to his own island of Coll.

Seal pup sleeping.

An epilogue to the story tells of a vision experienced by Columba in which he perceived that Erc was close to death. The saint immediately ordered his cousin, a senior monk, to take a gift of meat and grain to the dying man. Adomnán does not say where Erc spent his final days but we can probably assume the location was Coll. The gift from Iona arrived almost too late, on the day of Erc’s passing, so it was consumed at his funeral feast instead.

Among a number of interesting points in the story I’ve highlighted five:

1. The monastery of Iona claimed the right to cull seals on one (or more) of the small rocky islands off the Ross of Mull. This may have been one of a bundle of informal rights exercised by the monks along the shoreline on the east side of the strait, or it may have been a formal concession granted by a landowner. In another story, Adomnán makes it clear that the monks did not have free rein to take whatever they wanted from the opposite shore: Columba compensated a man called Findchán who was upset to find monks cutting branches on his land at Delcros, probably an estate or farm on the Ross of Mull. The wood was being shipped back to Iona as building material for a new guesthouse, but it was being taken without Findchán’s permission.

Grey seal female and newborn pup.

2. The island of the seals is described as a breeding-ground, a place where females come ashore to give birth (Adomnán uses the Latin phrase

generantur et generant). It must have been an extensive area, attracting large numbers of seals, to tempt a poacher like Erc to make a sea-journey of sixteen or seventeen miles. This might help to identify the location of the island, especially if it is still used by grey seals in the breeding season.

3. Archaeological evidence from excavations on Iona shows that seal-meat was on the monastic menu. The animals also yielded other useful products such as skin and oil. Sealskin is a naturally waterproof material, while the soft fur of the pups provides a warm lining for clothes. The sporrans worn with Scottish kilts are traditionally made from sealskin, although synthetic versions are less controversial (seal products have been subject to a European ban since 2010). In Adomnán’s time, Irish seal-hunters used a special harpoon called a murga (‘sea spear’) or rongai (‘seal spear’). Adult grey seals are large predators and can seriously injure any human whom they perceive as a threat. Erc moccu Druidi would have been well aware of this danger, but he did not sail to the Ross of Mull to challenge full-grown male seals (which can grow to 10 feet in length). His target, as Columba observed, was the breeding-ground where mothers and newborns would have been particularly vulnerable. British and Irish grey seals breed in the autumn, so Erc’s visit to Mull probably took place in October or November.

4. Erc does not seem to have been a person of high status. He owned a boat small enough to be turned upside down and used as a rudimentary shelter – it was most likely a small currach or coracle, a light but sturdy craft with a hull of animal skin. He was probably not a landowner or farmer, hence his need to hunt seals. Back home on Coll he had family or friends who valued him: when he died, they arranged a funeral and held a feast in his honour. They may have been members of moccu Druidi, ‘the people of Druidi’, the kin-group or clan to which he belonged. This group was presumably based on Coll and evidently spoke Gaelic rather than Pictish or British. Erc was seemingly a Christian, but not – as Columba points out – a rigid devotee of the Eighth Commandment (‘Thou shalt not steal’).

5. Erc lived on Coll and would have been answerable to a local lord there. He was not answerable to Columba on secular (i.e. non-religious) matters and could have refused the saint’s request to come to Iona. His acquiescence suggests that Columba’s authority as a spiritual leader was recognised by Christians on Coll. We might infer from this that any clergy working on the island in the late sixth century were members of the Iona brethren.

* * * * *

Notes

The story of Erc moccu Druidi appears in Book 1, Chapter 41 of Adomnán’s Vita Columbae. For this blogpost I have used the Andersons’ edition (1961; revised 1991) for the Latin text. The passages in English come from Richard Sharpe’s translation, published by Penguin Classics in 1995.

For Adomnán and his contemporary audience, the main point of the story was Columba’s miraculous power of farsight in knowing when Erc was about to die. Vita Columbae, like many hagiographical texts, is basically a collection of miracle stories testifying to the special status of the saint (and, by association, to the importance of his monastery and the authority of his successors).

My information on early Irish seal-hunting and on the archaeological evidence (animal bones) from Iona can be found on pp.302-3 of the Penguin Classics translation, where Richard Sharpe cites useful references.

Adomnán says Erc lived on insula Colosi, ‘the island of Colosus’. This is not, as was once thought, the isle of Colonsay. Scholars now accept that Colonsay has a name of Norse origin (probably ‘Kolbein’s Island’) coined long after Adomnán’s time. Its original Celtic name may have been Hinba, an idea I’ve discussed in an earlier blogpost.

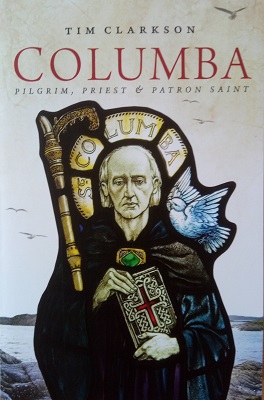

Erc and the seals get a brief mention on page 97 of my book on Saint Columba.

The photographs in this blogpost are copyright © B Keeling. They were taken in November 2013 at Donna Nook in Lincolnshire, a traditional breeding ground for grey seals. Hundreds of bulls (adult males) and cows (adult females) come ashore onto the beach each autumn. The Lincolnshire Wildlife Trust has a webpage for the Donna Nook Nature Reserve.

Seal pup near the fence alongside the visitor path at Donna Nook Nature Reserve.

* * * * * * *