Dame Ellen Terry as Lady Macbeth, 1889 (from a painting by J.S. Sargent)

Mael Coluim mac Cinaeda (‘Malcolm, son of Kenneth’) succeeded his cousin Cinaed, son of Dub, as king of Alba in 1005. The succession was apparently contested by the rulers of Moray in the person of Findlaech, son of Ruaidri, who lodged a rival claim for the kingship. Findlaech, the

mormaer (‘great steward’) of Moray, was described in the Irish annals as ‘king of Alba’ when they reported his death in 1020. His nephew Mael Coluim, son of Mael Brigte, died nine years later and was likewise accorded the same royal title by the annalists. Both men must have claimed the throne of Alba when its legitimate incumbent was Mael Coluim mac Cinaeda, who reigned from 1005 to 1034. On two occasions, then, the authority of Cinaed’s son was challenged by the lords of Moray.

The kingdom of Alba

The Moravians themselves appear to have been riven by internal strife. Rivalry between Findlaech and his brother Mael Brigte led to the former’s death at the hands of the latter’s sons. The most likely context was a military struggle for the mormaership. After Findlaech’s slaying in 1020 his murderous nephews – Mael Coluim and Gilla Comgain – ruled Moray for a further twelve years. Mael Coluim was the above-mentioned claimant on the kingship of Alba, the man whose death in 1029 was reported in the Irish annals. After staking his royal claim, as a rival of his namesake Mael Coluim mac Cinaeda, he seems to have appointed his brother Gilla Comgain as mormaer of Moray. But Gilla Comgain was in turn challenged by Findlaech’s son Macbethad, an ambitious individual who was soon to emerge as a key player on the wider political stage. In later centuries Macbethad found greater fame on a different kind of stage, being borrowed by William Shakespeare as the inspiration for his devious character Macbeth. In the meantime, the historical Macbeth made his first appearance around the year 1030, as a challenger to Gilla Comgain’s authority in Moray. This may have prompted Gilla Comgain to strengthen his own position with a political marriage, for his bride was a lady of high royal blood. Her name was Gruoch, daughter of Boite, and she was a close kinswoman of King Mael Coluim mac Cinaeda, perhaps his niece or the daughter of one of his cousins.

Gilla Comgain continued to rule as mormaer of Moray until his death in 1031 or 1032. His grisly demise was noted in the Irish annals:

Gilla Comgain, son of Mael Brigte, mormaer of Moray, was burned together with fifty people.

This was probably the final act in a bitter kin-strife that had started in the previous generation. Although the annalists do not say who was responsible for the burning it was surely the work of Macbethad, who thus became the new mormaer of Moray. In a politically astute move he quickly married Gruoch, Gilla Comgain’s widow, thereby linking himself to the royal dynasty of Alba. The marriage also made him stepfather and protector of Gruoch’s son Lulach, Gilla Comgain’s heir, who was probably a small child at the time. Whether Gruoch entered this union willingly or grudgingly is unknown, for the sources give no further information. If, as seems likely, Macbethad was the instigator of her first husband’s death, she might have been his reluctant bride. Alternatively, she might have regarded Macbethad as a useful match for her own ambitions. Did she perhaps play some part in Gilla Comgain’s downfall? Such speculation, although interesting, could tempt us to cross the line between fact and fiction, for Gruoch is the historical figure behind the ruthless Lady Macbeth of Shakespeare’s play.

Mormaers of Moray in the 11th Century

Macbethad’s career was as dramatic as any playwright’s narrative. Within months of his seizure of power in Moray he joined Mael Coluim mac Cinaeda, the king of Alba, in a pledge of fealty to King Cnut of England. In the

Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, which placed this event under the year 1031, Macbethad is described as a king. The label need not be taken at face value, for it is unlikely that he had launched a bid for the throne of Alba at so early a date. Indeed, he may have continued to rule Moray not as a potential rival to Mael Coluim but as a loyal subordinate or vassal guarding an important territory on the king’s northern frontier.

Gruoch’s kinship with the royal dynasty would have proved useful to Macbethad. It brought him closer to the centres of power and would have enabled him to forge useful alliances at the king’s court. His wife’s connections with the ruling elite undoubtedly helped him gather support for the coup d’etat which would one day elevate him to the throne. But he nurtured his ambitions slowly and carefully, biding his time until the right moment. Thus, after Mael Coluim’s death in 1034 brought his grandson Donnchad (‘Duncan’) to power, Macbethad gave his allegiance to the new king and played the role of loyal henchman. He eventually made his move in the summer of 1040, not long after Donnchad suffered a humiliating defeat at the hands of the English. The Irish chronicler Marianus Scotus, writing forty years later, gave a near-contemporary account of Donnchad’s fall:

Donnchad, king of Scots, was killed in the autumn, on 14 August, by his dux Macbethad son of Findlaech, who succeeded to the kingdom for seventeen years.

In this context, the Latin term dux (‘duke’) might be an attempt by Marianus to translate Gaelic mormaer. In a more general sense it indicates that Donnchad was slain during the revolt of a subordinate lord. It was this deed of treachery that prompted later Scottish writers, and eventually Shakespeare himself, to cast Macbethad in the role of villain. In an 11th-century context, however, the toppling of a king by an ambitious rival was a normal method of regime-change.

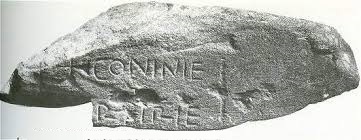

Her husband’s victory made Gruoch the most powerful woman in Alba. She was now the Queen of Scots, a position she may have coveted from afar during her years of marriage to two successive lords of Moray. As queen, she would have played an important part in the smooth running of royal business. She would have had her own entourage of courtiers and retainers, as well as her own network of clients and friends. At times she would have accompanied the king on his periodic tours of the realm, and we have documentary evidence of this in a charter to which she bore witness alongside her husband. The document in question recorded a gift of land to the monastery of Loch Leven in Fife. Its scribe began by naming the royal benefactors: Machbet filius Finlach …. et Gruoch filia Bodhe, Rex et Regina Scottorum (‘Macbethad, son of Findlaech …. and Gruoch, daughter of Boite, King and Queen of Scots’).

In late 1049 or early 1050, Macbethad embarked on a pilgrimage to Rome. This was not an unusual task for a king from the British Isles to undertake. Others had made the same journey before him, seeking forgiveness for past sins by visiting the Eternal City. Most royal pilgrims were in their later years, or had already offloaded the reins of power to designated heirs. Macbethad was certainly a man of middle age when he began his pilgrimage. From a rough chronology of his career we can deduce that he was around fifty years old. It is likely that Gruoch did not accompany him, and that she stayed at home to maintain a royal presence at court. How much authority might then have been delegated to her in Macbethad’s absence is hard to say but he must have trusted her to support his kingship while he was away. This is actually a key point, because potential royal claimants were surely lurking in the wings. The probability that Macbethad left his wife behind suggests that he had no doubts about her political loyalty. It might also suggest that he perceived little or no threat from Lulach, Gruoch’s son by Gilla Comgain, whose own claim on the throne she might otherwise have promoted.

Macbethad thus returned from Rome to find his kingship still intact. He resumed his reign and faced no serious challenge to his position for a number of years. His subjects clearly respected him, as did folk living beyond the borders of Alba. Ambitious warriors from other lands were attracted to his court, perhaps because he gave rich rewards for military service. One group of Norman adventurers, having been made unwelcome in England, travelled north to place their swords at his disposal. These men died in battle in 1054, fighting to defend Macbethad from an English invasion which succeeded in casting him from the throne. The architect of his defeat was Earl Siward of Northumbria, a powerful henchman of the English king Edward the Confessor. What happened to Macbethad in the aftermath is not recorded but he may have sought refuge among his kinsmen in Moray, unless he found a safer haven elsewhere. Wherever he went, we can be fairly sure that Gruoch and her son accompanied him. Siward, meanwhile, appointed a man called Mael Coluim as the new king of Alba. Despite his Gaelic name, this Mael Coluim was a prince of the Strathclyde Britons. His eligibility for kingship of the Scots must nevertheless have derived from ancestry, and his name seems to hint at mixed Gaelic-British parentage. His father was the king of Strathclyde; perhaps his mother was a royal princess of Alba?

Mael Coluim’s reign did not last long. His position would have weakened considerably after Siward’s death in 1055. With the menace of the Northumbrian earl removed, Macbethad was able to expel Mael Coluim and take back the throne. He ruled for a few more years until his own death at the battle of Lumphanan in 1058. His nemesis was Mael Coluim mac Donnchadha, a figure otherwise known as ‘Malcolm Canmore’ (Gaelic ceann mor, ‘big head’). Mael Coluim’s victory thus avenged the slaying of his father, King Donnchad, whom Macbethad had destroyed eighteen years earlier.

We do not know what happened to Gruoch in the wake of her husband’s death. Her son Lulach seems to have held the kingship of Alba for a few months until he, too, was defeated and slain by Mael Coluim. Widowed and alone, Gruoch may have found herself at the mercy of the new king. Her fate would then have depended on her usefulness as a dowager queen, a royal lady of wealth and influence – if indeed she could be persuaded to pledge allegiance to Mael Coluim. The fact that she was his kinswoman, a female elder of the royal dynasty, would not have guaranteed her survival. Against whatever political value she still retained was the threat she undoubtedly posed to the stability of the realm. She might, for instance, become a figurehead for disgruntled supporters of Macbethad, especially in Moray where Mael Coluim’s authority was unlikely to have been strong. So what were her options, if indeed she was not murdered, or chased out of the kingdom, or imprisoned in some dark dungeon? If she somehow managed to survive the upheavals of 1058 she may have been allowed to enter monastic retirement, becoming the abbess of a religious house to which she had been a benefactor in former times. Alternatively, she may have simply retired to one of her estates, in semi-exile from the royal court, quietly living out her remaining years as a relic of past troubles.

Probable ancestry of Gruoch, daughter of Boite.

* * * * * * *

References

Archibald Duncan, The Kingship of the Scots, 842-1292 (Edinburgh, 2002), p.32.

Benjamin Hudson, Kings of Celtic Scotland (Westport, 1994), pp.136-8.

William Kapelle, The Norman Conquest of the North (London,1979), pp.41-2.

Archibald Lawrie (ed.), Early Scottish Charters prior to 1153 (Glasgow, 1905), pp.5-6.

Alex Woolf, From Pictland to Alba, 789-1070 (Edinburgh, 2007), pp.247 & 255-65.

* * * * * * *