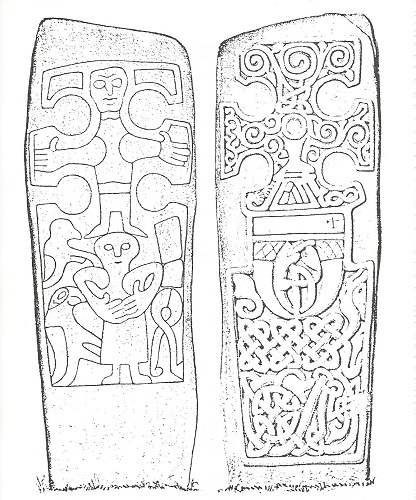

Early medieval cross-slab in Dunblane Cathedral (© B Keeling)

Two early medieval carved stones were discovered at Dunblane Cathedral during restoration work in the late nineteenth century. One is a broken rectangular slab with carved patterns along one edge only, the rest being unadorned. The other is a fully ornamented cross-slab, with carvings on front and back. Both stones were found under a staircase in the Lady Chapel or Chapter House but can now be seen at the west end of the North Aisle. They were probably carved in the tenth century and are usually regarded as late examples of Pictish sculpture. This may mean that they are not really Pictish at all, for the Picts appear to have developed new ideas about cultural and political identity at the end of the ninth century. Close contact between the Picts and their Scottish neighbours in the Gaelic West eventually led to the complete disappearance of ‘Pictishness’ and its replacement by ‘Scottishness’. It might be more accurate, then, to associate the Dunblane stones with the new, Gaelic-speaking kingdom of Alba which emerged around AD 900 in what had formerly been the Pictish heartlands.

The Dunblane Cathedral cross-slab stands a little over 6 feet high. Its carvings were described in detail by John Romilly Allen in an article published in Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland in 1881. Allen’s own drawings of the front and rear faces appeared at the end of the article and were reproduced twenty-two years later in The Early Christian Monuments of Scotland, his great collaborative venture with Joseph Anderson. The text below, taken from the entry for Dunblane on pages 315 to 317 of ECMS, describes the carvings on the rear of the slab.

‘A single panel, containing (at the top, nearly in the middle) a pair of beasts sitting up on their hind quarters, facing each other and with their fore-legs crossed; (at the right hand upper corner) a single spiral; (below the beasts on the left) square key-pattern No. 886; (on the right of this) a square figure with five raised bosses like the spots on a die; (next in order going down the slab, on the left) a small cross of shape No. 102A; (to the right of this) a figure resembling a keyhole plate as much as anything; (then) a horseman armed with a spear and accompanied by a hound; (below on the right) a circular disc ornamented with a cruciform device, there being traces of a very rudely executed key-pattern on the background; (at the bottom of the slab on the left) a man holding a staff in his right hand; and (at the right-hand lower corner) a single spiral.’

[Note: To illustrate similarities between sculptural styles in different parts of Scotland, Allen and Anderson used a numerical classification for the most common types of carving, e.g. ‘key-pattern No.886’]

Allen’s drawing of the Dunblane Cathedral cross-slab.

Assigning a precise historical context to the cross-slab is no easy task. Dunblane is in Strathallan, the valley of the Allan Water, in the former county of Perthshire. It lies on the southern edge of what is generally considered to have been ‘Pictland’ in earlier times. To what extent (if any) its tenth-century inhabitants still regarded themselves as Picts is a matter of debate. The rulers of Alba – descendants of the Pictish king Cináed mac Ailpín (died 858) – certainly identified as ‘Scots’ in the early 900s and many of their subjects no doubt followed suit.

The place-name Dunblane (Gaelic: Dún Blááin,’fort of Blane’) was originally Dol Blááin ‘Blane’s water-meadow’, both names being traditionally associated with the sixth-century saint Blane or Bláán whose main monastery lay at Kingarth on the Isle of Bute. One possible scenario is that monks from Kingarth, seeking a refuge from Viking raids in the ninth century, established a new community at Dunblane on a site later occupied by the cathedral. This early religious settlement may have been targeted by the Britons of Dumbarton, who are said to have burned Dunblane during the reign of Cináed mac Ailpín. The same monastery might also be the unidentified civitas Nrurim where, according to the Chronicle of the Kings of Alba, Cináed’s son Áed was killed in 878 (in this period, the Latin word civitas meant ‘major religious settlement’ as well as ‘city’ or ‘fortress’). Other sources place Áed’s death in Strathallan, so Nrurim might be an older name for the newly founded monastery of Dol Blááin, or perhaps a garbled version of it.

Unlike some other early medieval carved stones, the Dunblane cross-slab is easy to find. It is certainly worth seeing, not least because it shows how ‘Late Pictish’ stonecarving had declined from the high craftsmanship of earlier periods (compare, for instance, the Dupplin Cross of c.830). The cathedral is open all year round but it’s advisable to check beforehand if planning a special trip – see the link below.

* * * * *

Links & references

Record for Dunblane Cathedral on the RCAHMS Canmore database

Dunblane Cathedral opening hours

John Romilly Allen, ‘Notice of Sculptured Stones at Kilbride, Kilmartin and Dunblane’ Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland vol.15 (1880-81), 254-61.

John Romilly Allen and Joseph Anderson, The Early Christian Monuments of Scotland (Edinburgh: Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, 1903) [A facsimile reprint is available from the Pinkfoot Press in Brechin]

Chronicle of the Kings of Alba (extract from the entry for Cináed mac Ailpín) –

‘Septimo anno regni sui, reliquias Sancti Columbae transportavit ad ecclesiam quam construxit, et invasit sexies Saxoniam; et concremavit Dunbarre atque Marlos usurpata. Britanni autem concremaverunt Dubblain, atque Danari vastaverunt Pictaviam, ad Cluanan et Duncalden.’

[‘In the seventh year of his rule, he transferred the remains of Saint Columba to the church which he built (at Dunkeld), and he attacked England six times; and he burned Dunbar and captured Melrose. However, the Britons burned Dunblane, and the Danes laid waste to Pictland, as far as Clunie and Dunkeld.’]

The suggestion that the unidentified civitas Nrurim might be Dunblane was made by Alex Woolf on page 116 of his book From Pictland to Alba, 789-1070 (Edinburgh, 2007)

Photos of the two Dunblane stones (via the Canmore database)

* * * * * * *