Clach nam Breatann (© David Dorren 1998)

One of the main roads to the Scottish Highlands is the A82 which carries travellers from Glasgow to Inverness via Fort William. After leaving the outskirts of Glasgow, this well-known highway passes Dumbarton and Alexandria before running north along the side of Loch Lomond. The loch is eventually left behind as the A82 continues onward through Glen Falloch to Crianlarich and Tyndrum.

High up on the western slopes of Glen Falloch, on the opposite side from the picturesque Falls, stands Clach nam Breatann, ‘The Stone of the Britons’. Like a space-rocket ready to launch, this enigmatic monument leans up from its base to point towards the sky. The topmost piece or capstone rests on deep-set boulders that seem to grow out of the ground. These foundations are sunk so deeply in the hillside that they might indeed be a natural rocky outcrop. The whole assemblage sits on a conical mound of earth and stone which appears to be partly man-made, like a large cairn now covered with grass.

Clach nam Breatann (© David Dorren 2002)

Clach nam Breatann (© David Dorren 2002)

Tradition asserts that Clach nam Breatann marked the boundary between Picts, Scots and Britons. Its association with the latter suggests that it lay within their territory and therefore belonged to them in some way. Historians generally assume that it defined the northern limit of the kingdom of Alt Clut or Dumbarton (c.400-870 AD) and also of the successor realm Strat Clut or Strathclyde (c.870-1070). The assumption is no doubt correct, although we should also keep in mind the possibility that the stone simply commemorated a famous battle involving the Britons. In the nineteenth century, the Scottish antiquary W.F. Skene suggested that an unidentified ‘Stone of Minuirc’, scene of a battle between Scots and Britons in 717, may have been Clach nam Breatann. The geographical setting of Glen Falloch would certainly be consistent with a frontier clash between opposing forces from Dál Riata and Clydesdale, but Skene’s theory was only a guess and Minuirc remains elusive.

Clach nam Breatann (© David Dorren 1998)

I visited Clach nam Breatann some fifteen years ago. I had never seen anything quite like it before. Not only did it look imposing and ancient, it also had a strangeness, an eccentricity, that I found hard to explain. Since then, I’ve mentioned the stone in my book The Men of the North (with an accompanying photograph) and in several posts at this blog. I would like to make a return visit, to refresh my memory and to take more pictures. Getting there is by no means easy, for the approach involves a trek up a steep hillside over rough, boggy terrain. However, the effort is definitely worth it, especially on a clear day when the view is truly breathtaking.

Clach nam Breatann (© David Dorren 1998)

Clach nam Breatann (© David Dorren 2002)

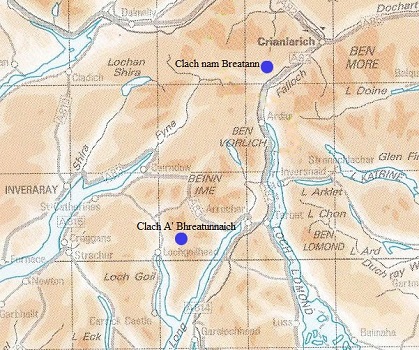

As well as re-visiting Clach nam Breatann, I’m keen to see another impressive landmark for the first time. This is a gigantic boulder known as Clach A’ Bhreatunnaich, ‘The Briton’s Stone’, a glacial erratic nestling on the southern flank of Ben Donich near Lochgoilhead. As with Clach nam Breatann, tradition asserts that this solitary megalith stands on an ancient boundary between the Clyde Britons and their neighbours – in this case, the Scots of Cowal. Both stones may in fact be part of a single frontier – they are, after all, only 12 miles apart. The possible course of such a divide was traced by the late Betty Rennie who published her findings in the Pictish Arts Society Journal in 1996 (see reference below). Rennie’s pioneering work on ancient boundaries has been continued by two of her former colleagues in the Cowal Archaeological Society – David Dorren and Nina Henry – whose research on the mysterious Druim Alban (‘Ridge of Alba’) was highlighted in an earlier post at this blog.

The following images of Clach A’ Bhreatunnaich give a good idea of its size and of its position in the landscape.

Clach A’ Bhreatunnaich (© David Dorren 2010)

Clach A’ Bhreatunnaich (© David Dorren 2010)

Clach A’ Bhreatunnaich (© David Dorren 2010)

Clach A’ Bhreatunnaich (© David Dorren 2010)

Clach A’ Bhreatunnaich (© David Dorren 2010)

Clach A’ Bhreatunnaich (© David Dorren 2010)

Clach A’ Bhreatunnaich (© David Dorren 1999)

* * * * *

Notes & references

I am again grateful to Dr David Dorren for allowing me to reproduce his photographs here at Senchus.

Elizabeth B. Rennie, ‘A possible boundary between Dál Riata and Pictland’ Pictish Arts Society Journal 10 (Winter 1996), 17-22.

Armand D. Lacaille, ‘Ardlui megaliths and their associations’ Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, vol.63 (1929), 329-32. [This article describes Clach nam Breatann and can be accessed via the PSAS online archive]

A link to my blogpost on Druim Alban.

Entries on the Canmore database for Clach nam Breatann (under its alternative name Clach na Briton) and Clach A’ Bhreatunnaich.

From the Annals of Ulster, under the year 717:

Congressio Dal Riati & Brittonum in lapide qui uocatur Minuirc, & Britones deuicti sunt.

(‘An encounter between Dál Riata and the Britons at the rock called Minuirc, and the Britons were defeated.’)

* * * * * * *

This post is part of the Kingdom of Strathclyde series:

* * * * * * *

How fascinating, Tim! Love these rocks and the half-remembered history attached to them. The second one particularly is magnificent. I am also interested in your reaction to the atmosphere of the first, Clach nam Breatann. What is the thinking about the stone itself – was it deliberately positioned there, or is it a glacial erratic (for example)?

” fascinating”: seconded.

Clach nam Breatann is on a hillside dotted with other huge rocks, so the first instinct is to assume it’s a glacial erratic. However, most experts seem to agree that the positioning of its constituent boulders suggests some measure of human intervention. The mound on which it stands certainly looks artificial, but only an archaeological excavation could say whether this is actually the case.

Reblogged this on THE BARCARII and commented:

A wonderful site close to a long hike into the back of Loch Oss that I did 2 years ago. This area is dotted with interesting landmarks worth a revisit.

How odd – I had recently decided to visit this area as I hike a lot in the hills here. I had previously hiked up from the Falls of Falloch into the back of Loch Oss and passed several ancient stone ruins along the Allt Fionn Ghlinne and when I examined them online later discovered the Clach nam Breatann stone. I will be revisiting it this week and will take pictures.

Thanks for dropping by and commenting. Wish I could travel up to see the Stone this week – the weather looks pretty good for photography.

Many thanks for this. Must visit both!

Cheers Peter.